|

Canterbury Colonists and

Emigrants

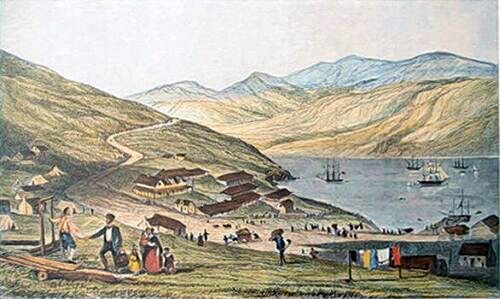

Port Lyttelton, showing the first four ships anchored in the harbour - Charlotte Jane, Randolph, Sir George Seymour and

emigrants landing from the Cressy, December 28th 1850

The fifth ship to arrive, the "Castle Eden" was built by Thomas Richardson of Castle Eden, England and John Parkin of Sunderland who established a shipyard at Old

Hartlepool in 1835. Up until the 1850s, most emigrants travelled on sailing ships, with an average voyage lasting 143 days. Steamships began replacing sailing ships as early as 1850 and shortened the voyage time. This made sailing ships obsolete by the end of the 1870s although some emigrants continued to choose sailing ships for nearly thirty years because of their cheaper fares. Living conditions on board were often primitive and space and privacy were both hard to come by. Few looked back on the voyage with fond memories - seasickness, inadequate food, lack of privacy, cramped living quarters, and spreading illness - an experience that seemed like an eternity. The Canterbury Association was founded in London 27 March 1848 in order to establish a Church of England settlement in New Zealand comprising a cross-section of English society. It was guided by Edward Gibbon Wakefield and John Robert Godley. Later that year, a party led by Captain Joseph Thomas arrived at the site of Lyttelton to prepare for the arrival of settlers. In late 1848, the Association’s land surveyors found what they considered the ideal site for the proposed settlement of Canterbury and for its chief town, Christchurch. In May 1849, official sanction was gained and the Association in London was notified.

By July 1849, the setting out of the port town and surveying of the Bridle Path and Port Hills were under way. On 3 January 1850 the Canterbury Association was authorised to dispose of 2.5 million acres between the Waipara and Ashburton Rivers, and the purchase terms were approved. The Association began recruiting emigrants, and by July 1850, preparations were well under way for the voyage to New Zealand. The "London Times" described the founding of Canterbury with evident satisfaction: "A slice of England cut from top to bottom, which sailed south to a new life in a new land!"Class distinctions were firmly rooted in the minds

of everyone in the early days of Queen Victoria's reign and repeated in

the conditioned life on board - From a cabin passengers diary :

"There are one or two of our fellow passengers who go among the

immigrants and make themselves familiar with them. The Captain is very

much annoyed as it tends to lower the dignity of the ship. One of them

absented himself from our meeting last night and was found amongst them.

The Captain felt himself insulted by his preferring their society to

ours. I have never spoken to one of them." Then there were “Emigrants” - mainly

agricultural farm workers, laborers, tradesmen, domestic servants and

young married couples - the majority of passengers. They

travelled in "steerage quarters" squeezed between the upper decks

and the bilges and slept in narrow, closely packed bunks. The area

was divided into three sections - one for single women who were berthed

in the aftmost section directly below the first and second class cabins

under the poop deck; married couples and children occupied the

mid-section and single men and boys, 12 and over, were in the forward

section. There were partitions between each section and each had its own

hatchway to the deck. They were required to restrict their movements to certain

parts of the ship and paid what they could afford for their £15 fare.

The shortfall was made up either by the Canterbury Association or by

their future employers travelling on the same ship. Emigrants were

required to be under 40 years old, to provide their own tools, and to

supply testimonials as to their qualifications, medical certificates and

certificates from the minister of their parish, countersigned by a

Justice of the Peace - their passage was either paid for by the

Canterbury Association, or by their future employers, travelling in the

same ship. Single men slept in bunks 6½ feet long by 2 feet wide.

Married couples shared a slightly wider bunk (3½ feet) and had a curtain

for privacy. This space was used not only for sleeping, but also for

storing everything needed for the voyage. There was a lack of fresh air,

and dampness was a constant concern. The boards of the berths were taken

out once a week and scrubbed and the floors under the berths and the

whole deck area was religiously scraped and holystoned at regular

intervals and chloride of lime sprinkled.

The women were expected to take a minimum stock of

clothing - 6 shifts, two flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two

pairs of shoes and two strong gowns and the English Women's Journal

advised working women not to leave without night-caps, aprons, bonnets,

pocket hankerchiefs and a shawl. The larger the stock of clothing, the

more comfortable the voyage with its extremes of heat and

cold and limited opportunities for washing and drying.

There was also intense educational activity

between the decks. The Association shipped a qualified

schoolmistress on board the Castle Eden. School hours were from 11 to 12

o'clock in the morning and 4 to 5 in the afternoon. Labourers who could

read, gave lessons in reading and writing to those eg men who

needed them and each ship carried a chaplain, a surgeon and a

schoolmaster, all paid for by the Canterbury Association. The doctor

received 10 shillings for every passenger safely delivered to Lyttelton,

but had to pay back 20 shillings for every passenger who died.

Passengers were required to restrict their movements to

certain parts of the ship depending on their class, however

seasickness and storms affected cabin and steerage passengers alike. One

emigrant recorded, “A good many are sick and vomiting.” Another recorded

that most people threw up after eating their very first meal on the

ship. Although some people adjusted to the constant rocking and

bouncing of the ship, others spent the entire trip nearly bedridden with

nausea. Days passed slowly for those afflicted as they struggled to keep

any food down. Many suffered from seasickness - the worst during the

first two weeks, but for some it continued for the whole voyage. During

storms, the door to the deck was latched closed, leaving passengers

with little light or fresh air. The stench of vomit and unemptied

chamber pots could be overwhelming. Constant jousting about from weather

and waves made even standing difficult on many days - passengers could not even stay in their narrow, closely packed bunks to

sleep, but went sliding about the cabin. The stench of vomit and

unemptied chamber pots could be overwhelming. Constant jousting about

from weather and waves made even standing difficult on many days. On the

worst days, passengers could not even stay in their beds to sleep, but

went sliding about the cabin.

Food on board did not contain a great deal of

variety. Minimum food requirements set by the British Passenger Act saw

basic food provided such as salted meat, flour, rice, biscuits and

potatoes, but steerage passengers had to cook it themselves. A large

table was fixed to the floor down the middle of the steerage area for

this. A bucket was supplied for washing and laundry.

The immigrants divided themselves up into messes

of about 6 people - the average size of the family travelling, and

each mess took it in turn to collect the issues of food from the purser

and take them at stated times to the galley for cooking. It was a long

and weary pilgrimage between the storeroom to the meal laid out on the

long table between the decks. Flour, currants, oatmeal and other dry

goods were carefully weighed and doled to each mess once a week (

usually Monday) and a small barrel of water. Before the others were up,

the breakfast mess cook had to take his pot of porridge along to a

galley that accommodated only three of four people and the ship's cook,

and as there might be more than a dozen messes of porridge to cook in a

great chaldron, it would be quite possible to spend more than an hour

waiting in turn at the galley stove. Food might suffer from under or

over cooking and in rough weather a wave might swamp the galley and put

out the fire. The rough seas had everything on the table sliding

and caused unexpected variations to the menu when the weekly provisions

would get all mixed together, such as salt, tea, coffee and treacle!

Two days the single men baked, afterwards the married

people and the young women had two days each, taking their

efforts to the galley to be cooked. Hot water was issued to each mess

before making coffee. Delay with the item did not matter as it had only

to be taken in tin mugs that could be put to the lips when cold,

accompanied by ship's biscuits, the hard tack, that often figured in wry

jokes. Midday, the main, was cooked in a common pot. Each mess

had a numbered wooden or metal token attached for identification to its

particular lump of meat and also to its net of preserved potatoes and

plum duff and boiled rice which was pudding. The evening

meal Seasickness was worst during the first two weeks, but

for some it continued for the whole voyage.The captain had to ensure

that each passenger received three quarts of water daily however its

quality was questionable. Passengers could bring additional provisions,

and many did. One passenger advised others on what to bring, remarking

that, “Coffee is much preferable to tea, the water being so bad, as to

render the tea rather insipid and tasteless.” To eat was difficult

- many used their trunks as tables. In rough waters, they struggled to

prevent these makeshift tables from sliding back and forth across the

deck.

Passengers passed the time at sea plotting the ship’s

course, writing letters and diaries, sewing, playing cards and games,

and dancing. Prayer meetings were held every morning and afternoon, and

there was a full church service on Sundays. There were also school

lessons for the children. Charlotte Jane left

first - departed Plymouth Sound, England early

morning on 7th Sep 1850 (abt. 154

passengers), followed a few hours later by

the Randolph (abt 217 -

Diary).

The Cressy left at

midnight (abt 155) and the next day, the 8th about

11am, the Sir George

Seymour weighed anchor with abt 227 on

board. (These numbers are not accurate because the surgeons, shipping

and emigration lists do not tally and also young children or those born

aboard were not given rations or counted as ticketed passengers Arrival: On the 16th of Dec. the first 3 ships

moved up the Lyttelton harbour. it was a summer's day and one of the

passenger's wrote "When we entered and sailed as it were, into the bosom

of the encircling hills who was there that did not feel at the time

that he could have gone through the fatigues of the whole voyage, if it

were only to enjoy the keen and pure gratification of the last few

days". As they neared the shore, they could see a line of road sloping

upwards across one of the hills, with specks dotted along it, which they

recognised as labourers at work. The place to some, appeared desolate -

no shops and only the barracks to go to.

The Charlotte Jane anchored at Lyttelton at 10am on Monday, Dec

16, 1850 and the Randolph arrived at 3.30pm. The Sir George Seymour

anchored at 10am the following day but the Cressy did not arrive until the

27th of Dec. having been delayed by bad weather, but these colonists too,

saw the harbour 'in a very favourable light". One passenger, from it's

deck, counted 15 whares which he, in his simplicity, at first took for dog

kennels! The ships brought about 800 people to Lyttelton. Most of

the passengers went straight to the immigration barracks that had

been erected to accommodate them, others camped for the first few weeks in

tents or built V huts of raupo and flax in the beautiful summer weather,

and as soon as possible, many of the settlers made the arduous journey up

the steep Bridle Path to the summit of the Port Hills and then down into a

swampy Christchurch to settle on the plains beyond.

Provisions were very short for some time after the settlers

arrived and were exceedingly expensive. Flour sold for £5 5s per bag of

200lbs, potatoes cost 14/- a kit and oatmeal 9d per lb. One of the

troubles of this time was the absence of coin: labour and produce had to

be paid for by goods and barter- that is, so much flour or sugar, or

an I.O.U. of the party receiving the labour or produce.

The ships lay at anchor for 9 weeks

during which time the passengers were able to go on board and get such

things as were available to them. Heavy goods were transported by boat down Lyttelton harbour, across the

shallow bar of the Sumner Estuary and then up the Avon River. A number of

families lost their possessions when boats sank crossing the bar.

The barracks had to be cleared out to accommodate the 204

passengers of the fifth ship Castle Eden under the command of Captain

Timothy Thornhill, which arrived on 14th Feb 1851 at Port Cooper (later

renamed Lyttelton . This meanta large proportion of people camped in the

open at Lyttelton and Christchurch until more substantial dwellings

could be built. (The Castle Eden had sailed from Gravesend 28th Sept.

1850, and from Plymouth on Oct 3 but heavy weather drove her back

- she finally left Plymouth Sound on Oct 18) One eye witness wrote of their first experience of a sou-wester

- "The weather changed very suddenly and a boisterous wind with a deluge

of rain found may very unprepared to withstand it. Tents were seen in

every stage of collapse, blankets, toitoi and fern careening madly through

the air, and the homeless seeking and finding shelter wherever a good

Samaritan could take them in." All persons occupying

the barracks in Lyttelton had, after a brief sojourn there to give place

to others, as ships arrived so quickly after each other and the

hillside near the barracks became dotted over with every conceivable kind

of hut, tent, and whare and sods. Many were glad to get away from the

barracks with the prospect of a little more freedom - one said she

"found it very trying and irksome living with her pots and kettles. She

was alluding to the one room (about l0 by 12ft) which was occupied by all

her family and had to do duty as bedroom, sitting-room and

kitchen. A printing press, type, and a

printing staff had arrived by one of the first ships, and by unremitting

exertions on the part of all interested the public had the advantage and

great gratification of very early welcoming the appearance of the first

newspaper, the Lyttelton Times. Published on Saturday, January 11th, 1851

and sold for 6d., there was a list of the retail prices for food; bread

was 7d. a 2 lb loaf; beef, mutton and pork 5d. a lb; ducks 4/- for a pair

( fowls were a shilling cheaper); eggs 2/- a dozen; ale 2/8d a gallon;

potatoes 5 a ton; milk was 3d a quart and fresh butter was 1/6d a lb. ( Mr

Ebenezer Hay, in these early days, used to carry 40 to 70 lbs of butter

every week on his back, d from Pidgeon Bay to Akaroa, returning the same

day over the 30 miles of mountainous bush track. William Guilford's first

job was there with his nephew, John Hay.) The appearance of Christchurch at this time

was certainly not inviting. The only means of communication was over the

Bridle Path, a rocky and precipitous path and then made through the swamps

that fringed the Heathcote and the Avon rivers. The pioneers had to carry

their household goods to the allotments they had chosen on the plains and

all their heavy goods had to be transhipped by small boats up the river

via the estuary whose banks were densely covered with flax, toitoi, fern

and raupo and this means of transport was very expensive and slow. One of

the Pilgrim Fathers used to tell with glee, the story of how he once,

early in 1851, hailed by a man struggling through the high scrub in what

was later Cathedral Square, and indignantly demanding to be shown the way

to Christchurch!

There were two houses on the Canterbury Plains and the farm

of the Deans brothers at Riccarton, with it's heavy crops and luxuriant

orchard was a strong contest to the boundless tract of treeless,

uncultivated land around. Many newcomers were disheartened by the strange life

and the hardships that faced them. Archdeacon Paul wrote "They landed and

they found the vaunted Canterbury Plains little better than a howling

wilderness. Their welcome was sung perhaps by the terrible sou-west wind

with it's driving rain and sleet. The rickety sheds in which they sought

shelter admitted the rain which splashed on their faces as they lay in

bed, and some of those who came out with little or no capital either in

the form of money or a pair of strong arms, might be ruined in a colony

even more rapidly than at home". Only a strong confidence in the future could have

upheld those men and women in the struggle they had to face. The women in

particular, had many trials and difficulties. John Robert Godley wrote - "

Before the arrival of the first ships two months ago, it was a grassy

plain unmarked by any sign of human footprint or handiwork, and now, early

in 1851, Christchurch is covered by at least 80 habitations of every

variety in form and material - tents, houses of reeds, grass, sods, lath

and plaster boards, mud and dry clay, besides a few that were merely pits

scooped in the banks of the river and one or two consisting of sheets and

blankets hung on poles." Jenetta Maria Cookse: Lyttelton

1852 When Mr Warren visited the Lyttelton settlement late

in 1851, and he was astonished and delighted by the appearance - " Wide

streets, neat houses, shops, stores, hotels, coffee rooms, emmigration

barracks, a neat sea wall and an excellent and convenient jetty with

vessels discharging their cargoes upon it, met our view;

whilst a momentary ray of sunshine lit up the shingled roofs and the green

hills in the background, until the whole place seemed to break into a

triumphant smile at our surprise." But his first view of

Christchurch, or rather of it's site, was a very different nature - " The

mountains in the distance were completely hidden by the thick rain, and

the dreary, swampy plain, which formed the foreground beneath our feet,

might extend, for ought we could see, over the whole island. The few,

small, woe-begone houses, which met my view, increased rather than

diminished the desolate appearance of the landscape." The site, chosen for the capital, was in part, a swampy plain,

with a slight fall seawards. soaked bv underground drainage from the hills

and intersected in every direction by springs and streams. The coast had a

strip of heavy wet land, usually some ten miles wide, and covered largely

with rank swamp grasses, higher than a man. There was watercress in plenty

and the luxurient growth had an abundance of pukeko and bitterns and it

was common to see flocks of up to 60 Paradise ducks flying overhead. Other

ducks such as teal and greys as well as spoonbills, were very common. The

swampy areas gradually gave way to dry stoney plain, covered with light

scrub and tussock. Wild Irishman, a very spiney plant grew as high as

3ft.6 ins with needle sharp points, and yellow flowers on a seed head that

went up from its base each year.

Beyond this again, were the lower foothills of the great

mountain chain on which tussock and scrub prevailed although the valleys

were often fertile and forested. The actual site of Christchurch and of

the rural allotments of the first land purchasers was what became known as

"dry swamp"- moderately wet swamp with native flax, toitoi cutty grass,

and sometimes heavy fern with boggy creeks running through it. Before

cultivation, this vegetation had to be stripped by hand with a mattock ( a

form of grubber) and when clear and burnt off, it could be ploughed either

with a horse or cow yoked to the single furrow plough, harrowed with a

tine harrow or sown by hand on the furrow. Often sheep were driven to and

fro across the furrows after sowing the seed, to act as harrows and

roller. When ready, the crops were reaped with a scythe or a sickle,

stacked and then threshed with a flail. Except for the areas chosen for the chief town and sea port,

all the land in the settlement was open to purchasers. The priority was

given to those who applied before the 25th of August, 1850 and was sold in

order of application. These first applicants were entitled to receive for

150 Pound, 2 land orders - one for a rural area of 50 acres, the other for

a half acre allotment in the capital, Lyttleton or a quarter acre in any

sea port town. |