Hidden Slide Menu on side Left

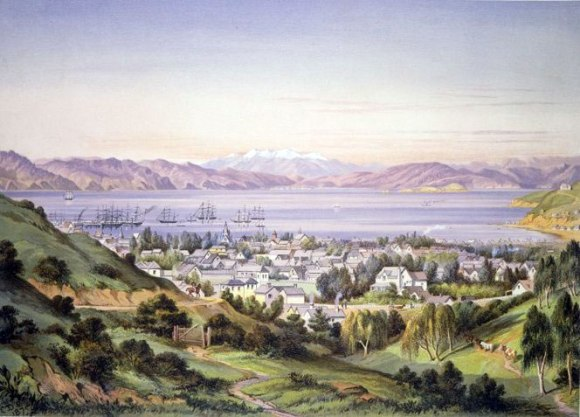

Wellington 1875 -

Painting by C D Barraud

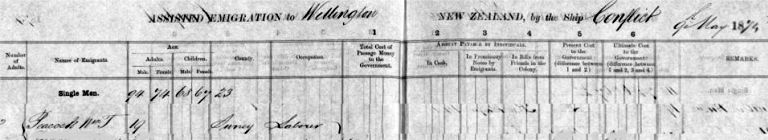

Wm T

Peacock, age 19Y, single man, a Laborer from Surrey

immigrated on the ship "Conflict".

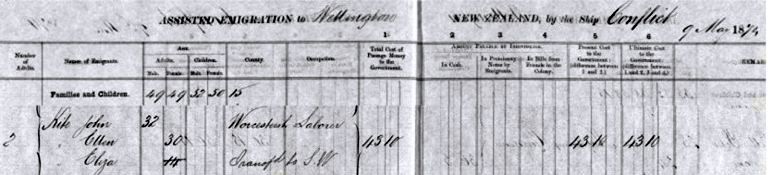

The Worcestor Kite family were also on board - father John 32Y, wife Ellen 30 and their daughter Eliza aged 14Y.  The "Conflict" was a twenty year old ship of 1171 tons, chartered by the Shaw Saville Co and Captain: Hardy. She was a full-rigged ship of 1171 tons, built at Liverpool in 1855. This was her first voyage to the Dominion, bringing out 450 immigrants. She left from Gravesend on on May 12, and arrived at Wellington, New Zealand on August 7, 1874, making a fast passage of 80 days. There are two documents held at the Alexander Turnball library which describe the voyage, one ĎFranklin, W. journal kept on board Conflict 1874" (see below); the other "Winter John: The Voyage of the Conflict 1874", a poem of some 60 stanzas. The following description represents a summary from these two sources. In addition, there are believed to be articles in the "The New Zealand Times" dated 4 and 5 August 1874 which tell of the Storm experienced by Wellington at the time of the shipís arrival. The Voyage of the Ship Conflict The ship

"Conflict" left the West India dock on the night of 7th May 1874 under

good weather, and was towed by steam tug out into the basin and from there

down to Greenhithe. Once the tide had turned they were able to continue on

down to Gravesend. Here they moored off the town opposite the pier where

sadly "they could see the Falcon public house but could not get the beer."

In fact no intoxicating liquor was made available throughout the whole of

the Conflictís voyage, an almost unique situation for emigrant ships of

the time, but one which resulted in "no misconduct or crime" being

reported in the captainís voyage summary. Emigration officers came aboard

at this stage and dispensed "suspense moneys" to all passengers our author

received the princely sum of three guineas.

Bedding arrangements had been worked out in

advance by the shipping company, which quite frequently didnít match the

individual desires of particular emigrants. Passengers were given no

flexibility in this area however. Then from each grouping a member was

chosen, by consensus, to carry out the onerous task of collecting and

assuming responsibility for the weekly allocation of the groupís food.

This included arguing with the authorities where it was felt that the food

was not in fit condition for human consumption. Also from each general

area an emigrant was selected and designated as "constable" to handle all

grievances and disciplinary matters. The Conflict was towed out

from Gravesend at 2:30pm on 9 May guided by the pilot, with "some

passengers showing sad faces and some gay." The tug left that night, off

Portland Bill, with the pilot who took with him their last letters to

families and friends. After the tug had cast off and before they had time

to put on sail the ship commenced rolling very badly and those on board

suffered an early and most uncomfortable bout of seasickness. Fortunately

things steadied down somewhat when the sails were up and the ship started

to make headway Over the next few days they sailed on through

the Channel, passing The Lizard on the 17th of May and then

progressing through the Bay of Biscay on smooth seas. The 17th

was also notable for the occurrence of the first birth on board, a girl.

At 9pm on the 18th the passengers for some unknown reason took

to singing, most loudly, on the deck such that the doctor felt obliged to

break up the late night revelries. He ordering the single men back to

their place in the forward part of the vessel before anything more unruly

ensued, and the group slowly and reluctantly dispersed. Apart from the

captain, the doctor played the most important part in maintaining

passenger discipline and emigrants were required to formally sign their

agreement to his authority prior to boarding ship. The Conflict was a fast ship, leaving all in

its wake during the whole duration of the voyage. All were clearly very

proud of its prowess in the water since this fact was mentioned several

times in both documents. On the 19th of May they struck their

first taste of really rough and wet weather, and to make matters worse two

children were hospitalised on that day with measles, a disease that was to

strike several others including adults over the next few weeks. They sailed past Vincentís Cape and crossed the

Tropic of Cancer on the 29th May. Lime juice was now available

on a regular basis to all passengers to help soothe their hot, dry

throats. A lime juice quota for the tropic was normal on ships of this

time, but rated a special mention by our two scribes. It was obviously

much appreciated by all. On the 3rd Ė 4th of June

there took place a most interesting entertainment; possibly it was

traditional at such times. Over a period of several days the seaman

constructed what was called a "Dead Horse", and it was duly hung from the

yard-arm and ceremoniously dropped into the sea, much to the amusement of

the emigrants. The equator was crossed at the unearthly time

of 3am on the 7th June and as a result no King Neptune ceremony

was held. Another result of the midnight crossing was, the crew said, that

the emigrants had all sadly missed out on seeing the "Line of the Equator"

a line clearly visible on the surface of the sea. I wonder how many

emigrants were taken in and saddened by missing this phenomenon. Porpoises

and whales were now to be seen. On the night of the 9th of June the

wind rose up taking away the jib boom and this required several days of

work to repair. It was now hot, but not unbearably so, since they had

frequent cloudy spells and a fairly constant cooling breeze. A homeward

bound mail ship passed on the other direction, assuring them that

authorities would be duly advised of the Conflicts progress and that all

aboard were well.The Conflict travelled south past Brazil and then turned

eastwards towards Africa. Sea birds were visible as they rounded the Cape

of Good Hope, and soon after passing the cape the ship commenced to roll

violently from side to side, spilling plates of soup onto the floor and

forcing people to hang on for dear life. Over the next few days the

weather turned cold and damp, bad, it was said, for rheumatism. It was

then that the first deaths occurred, and initially these were

children. The 15th at the 5:15pm saw the first

death, a small boy; it was said from bronchitis and consumption, followed

just under a week later by another. However on the plus side three babies

were born over the period 26th June to 7th July, the

first boy being given the name Conflict as was the custom, presumably for

just one of his first names. At 12pm on 10th July under stormy

conditions their cook, a coloured man named Joe, died from congestion of

the lungs. He was committed to a watery grave the following day, wrapped

together with a small girl who had died on that day. On night of the

14th July sailor named George Wilson fell from the mizzen

top-sail yard-arm and was never seen again and then on the 17th

of July one of the mothers died, leaving behind a small daughter and a 2

week old baby. A single man called Mullins from Surrey died a few days

later on the 24th. It was a bad time made worse, for it was now

a full three weeks since another ship had been sighted. The

24th July saw them passing by the southwest tip of Australia;

although the coast was too far off to be seen. The night of the 25th was very

stormy indeed, probably the worst weather yet, and the captainís bellowing

voice could be heard throughout the night. Many women were sobbing. One

sail, the mizzen top-sail, was carried away and another ripped to shreds.

Such were the vagaries of the weather that by 29th July they

were becalmed. There was a further birth, the fifth, on the

27th but this baby died after but a few days of

life. On the day of the 30th of July they

were told that they were now near land, New Zealand, and all crowded on

deck to see. Eventually land said to be Mt. Egmont was visible and on

1st of August at Latitude 40.5 and longitude 174 east they were

but a few miles from the coast of the south island. Head winds now came up

and together with strong currents made progress up and into Cook Strait

unbelievably slow, several days with little or nothing to show, and the

passengers becoming more and more dispirited. In fact at one time the ship

had to turn about and head out again until the winds were more

favourable. As they entered the strait another baby died,

the 8th death but not the last, the sister of the baby

succumbing shortly afterwards. Finally on the evening of Sunday

2nd of August at 7pm they arrived outside the harbour and

called for the Pilot while lying about a mile off the (Cape Palliser?)

lighthouse. Spirits rose once more. With the Pilots arrival they ran into

Wellington harbour the following day and anchored 6 miles off the town of

Wellington. A small boat came out with fresh food, but, because of the

rough, wet weather could not get alongside. Nor could it get safely back

again to shore, the boat eventually sinking in shallow water. On the 14th all but 24 of the

families went ashore on a steamer and finally, on the 6th, the

ship got alongside the wharf and the remainder went ashore SUMMARISING: One report that 10 people perished

during the voyage, 3 adults and 7 children, while the other 11 people, 3

adults and 8 children. There were 5 births. The land to land passage

duration was 80 days, with no other ship being seen over a continuous

period of 37 days. The last land actually seen before reaching New Zealand

was the Canary Islands. Winter John: The Voyage of the Conflict

1874"

Evening Post: 6 Mar 1937 - VOYAGE

TO A NEW LAND (By "Spunyarn.") The log

of a passenger written during a voyage to New Zealand in 1874, which

is of interest, not so much because of the insight it gives into

conditions of travel in those days, but because of the impressions

recorded by the immigrant when he landed in the country. The traveller who made "the

voyage was Mr. W. Franklin, junr., and he left England, accompanied by his

wife and four children, on May 8, 1874. On May 7 of that year Mr. Franklin

went on board the ship Conflict in the West India Docks. The ship left

the jetty the same night for the basin, and the next morning the tug took

her as far as Greenhithe, where she waited for the turn of the tide,

proceeding thence to Gravesend. Here emigration officers came on board,

paying the passengers their suspense money. No friends were allowed on

board. On the 9th the ship was towed from Gravesend in the afternoon,

and the tug left her the same night. The vessel rolled about very much

previous to-getting sail'on her, and nearly all the adults, were seasick.

On the morning of May 17 the first birth occurred, a baby girl being born

to one of the passengers. Between 9 and 10

o'clock one night the passengers were singing on deck, and the doctor ordered the single men forward to

their own. part, of the ship, and to cease their noise, as it was late.

They did not obey, so the captain ordered part of. the crew to man the

force-pump used for washing the decks to clear them, but it was not used.

Passengers were supposed to be in bed by 10 o'clock, and up not later than

7 a.m. The 19th was the first rough day and two children were in hospital

with: the measles. Three vessels were sighted that day. The tropics were entered on May

29, and on June 3 it was recorded that a passenger took ill with the

measles, which was to prove a terrible scourge during the voyage. Two days

later, the seamen finished . their "dead horse" (month's pay-in advance),

and had a procession round the deck, a stuffed horse, Billy-go-easy on his

back, and all the crew dressed up as gravediggers for the funeral of the

horse. Last of all they hung him at yard-arm and then dropped him in the

sea. They then went to the captain for grog. The Line was crossed on the

7th, there being no shaving or any- fun. ■</p><p>The following day the jibboom went by

the board in a heavy squall. Mr. Franklin was on deck at the time, and had

gone up to shut the hatches down, as he expected rain. He had just

finished when the squall came on, and was forced to hold 'on to the meat

casks, these being the nearest things at- hand, while the deck was at an

angle of 45 degrees. A,,new boom was rigged up during the two next days.

On the 15th a baby died with bronchitis and consumption, and was buried on

the 16th. On the 20th a child died, and on the 16th a second child was

born. On the 29th. the third birth occurred, and on July 7 the fourth. Joe

the black cook died on the 10th from congestion of the lungs, and the

following day a child died, it and Joe being.buried. LOST OVERBOARD. On the 14th

it was rough and dry, and a .child died at 7 p.m. A seaman fell overboard

off the mizzen topsail yard-arm at 8 p.m. while shifting the ventnor

brace, the <

ship going 15 knots at the

time, it was too rough to help him. On the 15th the dead child was buried,

and on the 17th a: woman died, being buried a day later. On the 24th one

of the single men died, and was buried next day. The mizzen topsail was

carried away in a heavy squall at 3 a.m. on the 26th, and on the 27th the

fifth birth occurred, but the child died within a few days. Mount Egmont

was sighted on July 30. On August 1 the

ship got within a few miles of part of

the South Island, and on August' 2 arrived off

Wellington harbour at 7 p.m. and

signalled for a pilot who came off after dark. On the following morning,

after anchoring about a mile from the lighthouse, she slipped her cable

and ran into the harbour, dropping her other anchor six miles off the town

of Wellington,

just in time, as the wind went round again. A boat came off

shore with fresh food, but it could not get alongside and could not get

back to shore, sinking in shallow water. .The

ship got alongside the wharf and

all went ashore on August 6, the goods being sent up to the barracks. The

chronicler noted: "Our depot is on top of a hill like the grandstand on

Brighton downs; they give us plenty of grub here; I'm getting quite fat

.... I went after a job on Saturday, the Bth, and went to work on Monday

at a large stationer's; they do the Government binding; the wages here are

£3 to £3 10s. Houses, two rooms, are from 10s to 15s per week; beef, prime

4d per lb, mutton sd, very thin stuff, bread 7d. . . . We have arrived

here in the worst month of the year; out-of-door work has not begun yet;

this is the wettest part of the year, and the dearest. "NICE QUIET PLACE." "Wellington is a nice quiet place, about two

miles long, close to- the beach, hills behind, higher than the South

Downs, and very lumpy; the people say the ground has risen 4Jft in the

last ten years with earthquakes. Houses painted white, the larger ones

covered with galvanised iron. Geraniums grow-8 feet high here in a wild

state, and at Hull (Hutt?) they grow up the front of the houses like

vines; they make hedges of fuchsias; both bloom through the winter. "I

don't advise bookbinders to come out here (the diarist was a bookbinder).

Labourers that work in England for 12s a week, or navvies that PAGES FROM AN EMIGRANT'S LOG work

for 3s or 4s a day get the advantage out here. The wages were Bs, but now

7s per day for pick and shovel men. The agent in s London told us that if

we did not get work privately, the Government would employ us at 5s to 8s

a day; it is a lie. Some of our single

men went up country and could not get work; they are now working for

private persons felling timber in the bush, and get 3s to 4s a day,

working very hard, and £2 to pay for tools; bread lOd, no butter at all;

very bad indeed, great discontent. All the people here are money-grubs.

Coals are £2 5s per ton, wood 17s to 18s per cord; wood for building is

dear. We get plenty of watercresses, winkles, mussels, and oysters for the

trouble of fetching them. The fish wait in the bay to hang themselves on a

bunch of hooks as soon as you throw them in the water. The natives are

very civilised, dressed like us, and got lots of money; most of the land

belongs to them. . . . The houses in general are badly off for garden,

ground being so valuable here The streets in some parts are lit

with gas, and others with American rock oil, like paraffin. The Government

threaten to put us under canvas if we don't get houses before the other

two ships arrive; fine thing that for children, as it rains here very heavy. I must tell you what the barracks are like; they are composed of several

houses divided by partitions of about seven feet high into small rooms,

one to each family, one fire to each house; that is better than the

old Conflict, not a bit of fire there for anyone only in the cook's

galley. |