|

Wattie was born 15/10/1908 at Waimate, the 2nd child

born to Arthur and Roseanna Pelvin and was baptised at

the Waihao Anglican Parish Church on the 12th November. At 5

years of age he contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalised. His

condition was serious and resulted in a lung having to be

collapsed, a rare operation at that time. Wattie made a full

recovery and commenced his schooling as a new entrant at

the Redcliff School on 6/3/1914, attending for about 6

years and for 6 monthsattended the Tawai

school travelling with his brothers and sisters in a horse and

gig.

In 1920 the family moved to

Timaru where Wattie attended the Waimataitai school and had two

years at Timaru Boys High School. He was a keen sportsman,

particularly a long distance swimmer, and his holidays were spent

swimming across Caroline Bay and back. He left school in 1925 and

became an electrician's apprentice. Unfortunately his employer

emigrated to South Africa three years later which meant Wattie could

not finish his training.

In 1929 Wattie's parents

returned to farming. They purchased 500 acres at Totara Valley

and here Wattie worked as a teamster on his father's farm for seven

years. An excellent pianist, it was during this period as a

ploughman he formed a band called the "Footwarmers" with two friends

- Wattie on the piano, Eugene O'Connell on banjo and Norman Fenwick

on violin and played at dances all over the district. The

1930's were incredibly social years - children and babies came

with their parents to the local dances.

Wattie moved to Wellington

in 1936 to work as a casual labourer - "seagulling" on the

wharf and here, on the 27th March 1938 he married Ivy Josephine

Willoughby, whom he had known at Geraldine. Their daughter

Patricia Anne was born a year later.

Wattie's volunteered for

service in the Army in 1941 after war broke out . The childhood lung

operation made him ineligble for

overseas service so Private Walter Pelvin, Army

Registration No. 496685 was assigned to serve within New

Zealand at the POW camp at Featherston - first as a

carpenter to assist in it's construction and afterwards, he was

asked to stay on as a guard. He was a popular camp member with

his skills as a musician, and played piano whenever the

opportunity arose.

The fateful

morning, February 25, 1943, Wattie was rostered for guard duty

in No 2 Compound. No details of how his

death occured were given to his mother - she stated to a son that

Wattie in a letter from the camp, told her the

Japanese arrived in such poor condition, he did not think they would

prove too much trouble. It was only after the war family learnt how

he had died three days later.

A popular man at the

Featherston camp, his death left his friends in shock.

Officers and men of the camp lined the route to Featherston when the

funeral cortege of Private Pelvin left the camp and a memorial

service was held there on the Sunday evening

following .

Walter Pelvin's burial

service was led at St Mary's Church, Geraldine on March 2, 1943 with

full military honours. He was interred in Geraldine

Cemetery, the only New Zealand soldier killed "On active

service" at home during WW2.

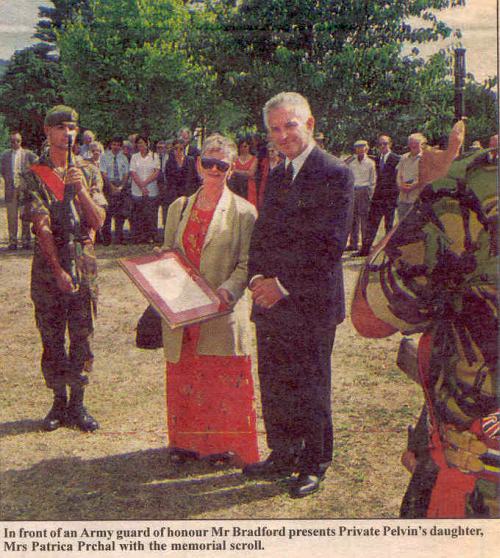

Three kilometres north of

Featherston on the morning of 28 February 1998, 55 years after the

tragedy. Defence Minister Max Badford presented the family of

Private Walter Pelvin with the New Zealand Memorial Scroll, awarded

to next of kin to servicemen who died in World War 2 to his daughter

Patricia Prchal who had been only 3 at the time. A plaque erected to

his memory is set in a concrete plinth opposite the ruins of

the former camp.

Speech Notes: Hon. Max

Bradford, Minister of Defence.

Saturday 28 Feb 1998 11.30

am

Memorial Scroll Presentation to

the family of Walter Pelvin, New Zealand guard

killed during the Japanese riot at Featherston POW Camp 1943

Your Worship, councillors, members of Private

Pelvin's family and the Featherston community.

I am honoured to be asked to make a

presentation to the family of Private Pelvin.

Although there was no fighting in New Zealand

during World War II, there more than 1,300 war graves spread across

the country. of men and women who died during training, through

accidents, or in hospitals from injuries they received in fighting

and memorials like the one here to Private Walter Pelvin, who 55

years ago today, died here at the age of 34 in the service of his

country.

The Prime Minister of the time, the Rt Hon

Peter Fraser informed the country that

ďA serious disturbance

occurred in a Prisoner of War Camp following the refusal of a group

of 250 Japanese prisoners to obey the orders of the camp

authorities. The prisoners were armed with stones, tools and

improvised weapons, and they rushed a small group of guards,

ignoring a warning shot by the officer in charge.

The guards were forced to open fire and

tragically 48 prisoners were killed and 63 wounded. Two officers and

five of the guard were injured, one guard having since died.

That Guard Private Pelvin, passed away at

Greytown three days after being injured by the ricocheting gunfire.

The story is not well known.

Four compounds housed the 800 or so Japanese

POWs. 500 in Number 1 compound were non-fighting labourers, resigned

to sitting out the war in the camp. Numbers 3 and 4 compounds held

small groups of officers or prisoners.

But on that hot February day Number 2

compound housing 290 combat trained Japanese sailors also contained

two officers who had slipped out of their compound un-noticed and

were agitating the sailors to riot. At 8:30 in the morning the

prisoners, who had taken kitchen knives and tools, refused to parade

for working duty. By 9.30, New Zealand NCOs and soldiers were formed

in a double line facing the sullen prisoners 15 metres away.

Attempts to remove the two Japanese officers by unarmed guards led

to removal of just one of them. A second attempt failed, as did a

third. The remaining Japanese officer, Lieutenant Adachi, remained

hid amongst his sailors. The guards withdrew but the situation

remained tense.

Two hours later the camp commandant feared

the disobedience would spread and worsen. The Adjutant called for

Lieutenant Adachi to surrender. His refusal was answered with a

warning shot from the adjutant's revolver over the prisoners heads.

The prisoners responded with a hail of

stones. The adjutant shot and wounded Adachi in the shoulder and the

250 prisoners armed with knives and crude weapons yelled with rage

and charged the 34 guards. The New Zealand guards had no choice but

to open fire. The shooting lasted only 30 seconds, and when the

chaos cleared 48 were dead.

It later became clear from the prisoner's

preparation of weapons that they fully intended to overpower the

guards, seize their rifles and escape. A powerful group of 250

trained and armed Japanese loose in New Zealand would have had even

more tragic consequences. The guards took the right action, and held

fast to their duty.

I sometimes talk of duty and service to the

nation when being interviewed by journalists about Defence.

Unfortunately service to one's country, one's community, or even to

one's fellow man is a concept that often doesn't receive enough

attention in today's modern culture.

The Governmentís recent decision to send our

young servicemen and women to the Gulf and into what we thought

might become international military action was not easy to make.

These decisions are not taken lightly or through any political

expediency.

I was humbled to see the sense of fellowship

amongst the service personnel and their families when I farewelled

them last week. I was impressed by the sense of pride and dedication

towards the task they have been asked to carry out on the nation's

behalf. I saw the same dedication and sense of duty when I visited

our personnel helping to restore peace to Bougainville

This same sense of comradeship, loyalty, and

sense of duty are values openly displayed in our military, and these

are values which Private Pelvin and his fellow soldiers were called

upon to exhibit here 55 years ago.

During his service, Private Pelvin was

awarded the War Medal and the New Zealand Medal. Because his death

was in New Zealand he was not eligible for the Memorial Cross

This Memorial Scroll is a mark of gratitude

from the Government and people of New Zealand to the family of

Private Pelvin, recognising his death in the service of the nation.

Walter's sister Rose

Oakley and brother Les Pelvin with Max Bradford

|