Scenes of Emigrants at Blackwall

Pier:

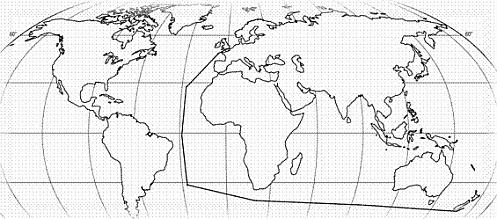

Route followed by sailing ships to New Zealand

Huntress: Departure 18 Dec 1862; Arrival Lyttelton 21

Apr 1863 Huntress: Departure 18 Dec 1862; Arrival Lyttelton 21

Apr 1863Benbow: (Src. The Benbow

Family Tree written by Catherine Lincoln, 1973)

Filled with optimism about their future in New Zealand,

William and Mary left with their family, Ann, James, Sarah, Elizabeth

and baby William Charles, for London then Plymouth where they were to

board their ship. Their 770 ton ship had 313 passengers on board and was

sailed by an experienced sea captain, Captain Barron who had previously

sailed ships to New Zealand.

Along with their treasures

and necessities, William and Mary brought seeds, fruit pips, nuts and tree

cuttings. Mary had a bundle of spring bulbs, snowdrops, irises, crocuses

and tulips. Cargo space was rationed but immigrants were encouraged to

bring as much as possible. With water on the voyage rationed, William

would go without his ration in order to keep his cuttings alive. Some of

the folk had brought livestock instead of household

goods.

Sarah Benbow had her 7th

birthday on board and she remembered well the Christmas puddings being

boiled in sea water and that no-one could eat them - apparently the storms

had swished salt water over the water tanks.

They had very heavy

weather in the English Channel and some violent seas till they reached the

equator 60 days after leaving Plymouth. From then on they made fine time

but did not sight land until they reached New Zealand. Near Timaru

they again suffered severe gales and the captain decided to put into

Lyttelton instead. They had been at sea for 4 1/2 months, a great test of

endurance and courage. Any hardships that came after probably felt

trifling compared to that long difficult voyage. PS: Son baby William died during the voyage. William Robert Keay and John Alexander Keay, his brother, were sent out on the 'Huntress' to work as farm cadets. He wrote a manuscript entitled "Extracts from the Reminiscences of W.R. Keay." These extracts below were published in the "Timaru Herald" in 1959 and reprinted in "Sherwood Downs and Beyond" by Connie Rayne of Oamaru. "After a few days of fine weather

the good humour and pleasing anticipations of all were restored. Crossing

the Bay of Biscay, the great height of the waves and the valley-like wide

spaces between were a source of much wonder.The wind continued favourable

to within near the equator, where the ship was becalmed for about two

weeks. The intensity of the heat was an uncomfortable experience. A 15ft

shark was caught. The boats had to be used to tow the ship into clear

water.

The first mate was popular but the

captain and some of the other officers were not.That was the origin of a

quarrel with menacing possibilities between the officers, crew and some of

the young men, who resolutely refused to accept the nauseous favours of

Neptune and his satellites. The lower deck between decks was crowded with

men, one of whom was grabbed by the sailors and a fierce struggle ensured,

the body and legs of the young fellow being cruelly handled before the men

completely overpowered the sailors. Many of the combatants were badly

bruised and their clothing torn or stripped from their bodies. The crew

was deprived of the fun expected and were not in an amiable mood. The

tactless captain, instead of allowing the dispute to cease, ordered the

men down to their quarters, saying as they would not join in the

sport to allow themselves to be plunged overhead in a vile, evil smelling

liquid and then shaved with a formidable bar of iron with cruelly jagged

edges, he would not allow them to look at others doing so. But the men

refused to go below. Two brothers had many shotguns and much ammunition

and the captain trained a cannonade on them threatening to blow them to

Hades. A few of the men brought up the firearms and defied the captain,

virtually holding possession of the ship, until the first mate, who had

previously interfered with the passengers, spoke in a kindly but

determined manner, who at once put away their weapons.

Days after leaving the equator, a

terrible cyclone was encountered. The ship was hove to and shipped many

seas. smashing boats and parts of the cooks' galley. The passengers were

all locked in their quarters, but William managed to escape and saw the

mountainous waves, and the sea white with foam. After the furious wind

ceased the sea became quite calm, and a wonderful and appealing spectacle

ensued. The surface of the sea was quite smooth, dark blue, and had an

oily appearance. There were no undulations. Everywhere the water was

rising vertically in huge cone-shaped heaps, then falling exactly to their

base. The good ship's timbers were creaking dismally, and also began to

leak. The ship reared almost perpendicularly - bows or stern up or down,

also rolling sideways, and all ways, in a most alarming manner. Only that

the ship's structure and materials were excellent, she must have

foundered. That was the opinion of the officers and crew, many of whom had

had years on the ocean. A new foremast was erected. A fair wind came and

the turbulent waters soon regained their natural form. Rapid progress was

made to the south, in favourable weather at night."

William always tried to remain on

deck. On one occasion, William had been listening to the yarns of a

regular old shell back named Old Bill. His vernacular was free and foul.

He was the watch at the bow and had been sleeping. William rose to go to

his bunk, and looking ahead saw to his amazement, a semicircular bay with

many lights and land showing distinctly. He instantly woke Old Bill who,

after seeing the land ran aft, and in quick time the stern of the ship was

facing where the bow had been. Old Bill threatened to throw William

overboard if he told anyone. It seemed a very narrow escape from

disaster.

William saw many whales spouting,

also many birds including albatrosses gliding through the air without

perceptible motion of the wings. Those that were caught vomited on deck.

Many of the little Cape Pigeons and stormy petrels etc followed the ship.

Flying Fish came on board. WIlliam caught several dolphins and admired the

beautiful coloured skin tints as they were expiring. The dainty nautilus

were always objects of admiration as they gracefully floated

past.

The voyage was becoming monotonous

when crossing the southern seas, only varied by singing and dancing. The

English conconcertina was the only musical instrument on the ship. There

was a pugilistic encouter with bare fists between a little man and a big

man, and fought in the good old English way to allow the weakest to have a

sporting chance. The combat ended in a draw. There was excitement over a

fight about equal in strength, and the struggle continued until the

butcher conquered, much to the delight of the onlookers. The mate was the

aggressor.

With one or two exceptions, the

passengers were a superior class, agreeing well together. There was much

discontent about the way victuals were cooked. The chief cook was a surly

tempered individual, and would persist in boiling the salt junks and duffs

in a mixture of sea and fresh water. Getting no redress from the captain

or the officers, the men in a body approached the cook about the matter,

and the dispute culminated in a fray in which the cook gave one of the men

a very serious wound near the eye with his long fork. He was instantly

seized and plunged head down into a cask nearly full of slimy grease. His

reappearance from the slimy depths was greeted with shrieks of laughter.

He became mentally affected and had to be confined until the voyage

ended.

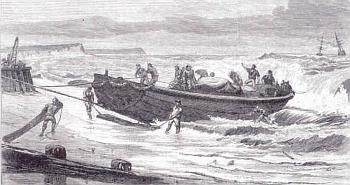

A new lifeboat was aboard for

Timaru, also agricultural implements, but a fierce southerly storm

prevented the ship from approaching the roadstead, which was then, and

many years after worked with surfboats.

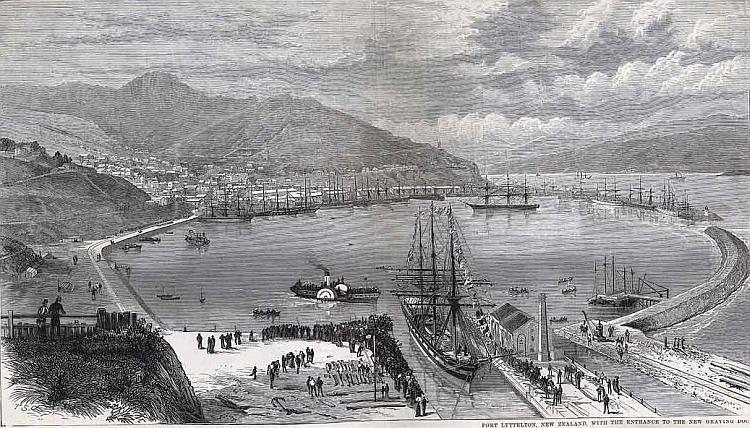

"The good ship having suddenly

disappeared in the furious storm from the view of the expectant onlookers

on the land, prayers were offered in the churches for the ship's and

passengers' safety but two or three days afterwards the ships anchor was

dropped inside Lyttelton Heads.

The snow on the Southern Alps

caused some weeping among the women, fearing they had been deceived by the

glowing accounts about NZ, discribed in a book "A land of pure delight,

where peaches grow on trees and roasted pigs came crying out, "Oh, eat me

if you please."

William Keay thought that the

captain was summoned for exceeding his duty and also for cruelty

and was fined. Some five sailors slipped down the bowsprit and swam

safely to the shore. They were lucky as the Huntress left Lyttelton

for Callao, South America (port of Lima, Peru) and was lost at sea. One

single man died from exhaustion when climbing the Port Hills, another was

killed a day or two afterwards after being dragged by a horse." (End of

William Keay's Diary)

Lyttelton Times, 18 April 1863: Captain Boyd reports that he sighted a large ship apparently standing in for Timaru at an early hour on the morning ot the 16th. It is just possible we may have to announce that this ship turns out to be the Huntress, so long looked for by anxious friends; she is out of Timaru 125 days, and has to call in with Government immigrants.

Lyttelton Apr 28 1863 - Source: London Illustrated News

Lyttelton Times, 22 April 1863

ARRIVAL OF THE SHIP HUNTRESS. We can imagine their relief, as our Benbow family stepped ashore after the storm-racked voyage and the memory and heart-break experienced with of the loss of their

infant son whose canvas-shrouded small body had been slipped over the

ship's side. But now, all this was behind them and room was found in the

New Zealand Company's immigration barracks and trunks and belongings were

unloaded and they awaited arrangements to be made so they and others

could be taken by coastal shipping back to Timaru..

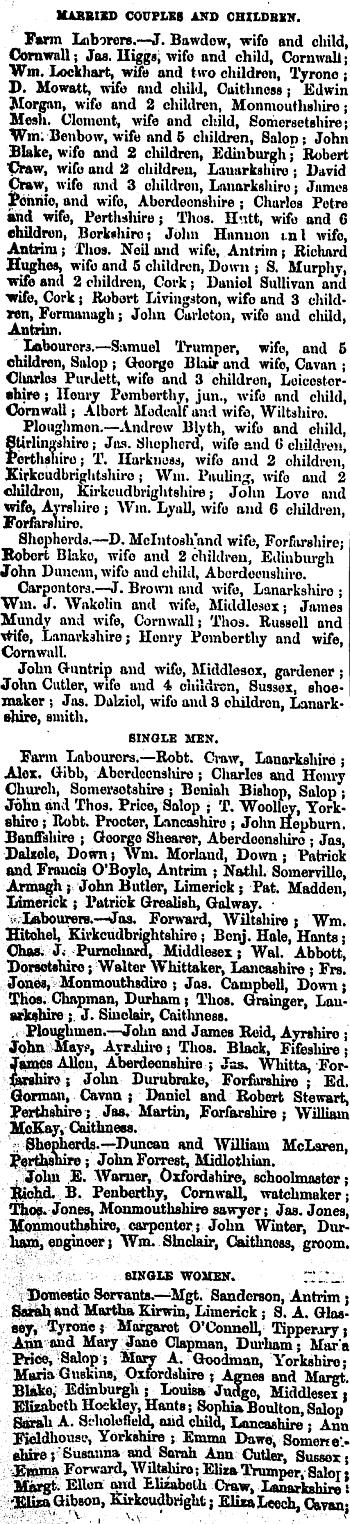

Lyttelton Times, 25 April 1863: SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE: LYTTELTON. arrived on April 21, ship "Huntress", 776 tons, Barrow, from London. Passengers� Cabin: Rev. F. Tripp, Messrs. Hoggard, Cook and Ainsworth. Second Cabin: Mr. and Mrs. Pilbrow, Mr. and Mrs. Lippett, Miss Ellis, Mr. and Mrs. Russell, Mr. and Mrs. Smith and son, Mr. and Mrs. Dickson and two children, Messrs. Whiteford, Bound, Wedderspoon, Russell, Butterworth, Keny, Bonnington, Stokes, Spridgeon. Milns, Hamilton, Jeffries, Lane, Murphy, Woodhouse, and E. H. Marshall (surgeon); also Government immigrants equal to 222 statute adults. Lyttelton Times, 2 May 1863: The "Lady Bird" sailed yesterday at half-past 4 with the passengers per "Huntress" for Timaru. She had the new life boat in tow. May 1, "Lady Bird", s.s., 220 tons, Renner, for Dunedin and intermediate ports. Passengers�For Akaroa: Messrs. Pentridge and Middleton. For Timaru: Messrs. Pilbrow, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Mr. and Mrs. Hughes, Mr. and Mrs. Russell, Miss Chapman, Miss Ellis, Miss Campbell, Messrs. Whitford, Tippitt, Fieldhouse, Whittaker, Winter, Proctor, Campbell, Russell, Benbow and family. For Dunedin �Mr. and Mrs. McDonald, Mrs. McQueen, Messrs, Wright, Chapman, Pike, Buchanan. Lyttelton Times, 16 May 1863 Timaru: The "Lady Bird", s.s., 220 tons, Capt. Rentier, from Lyttelton, arrived at Timaru early on Saturday morning, May 2. She brings the life-boat, so long expected, and the passengers come down are all from the Huntress, viz., Mr. and Mrs. Pilbrow, Mr. Whitford, Mr. Lippett and child, Miss Ellis, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Messrs. Whitaker, Winter, Proctor, Mr. and Mrs. Russell, Mr. and Mrs. Hughes and 5 children, Mr. Campbell, Mr. Russell, Mr. and Mrs. Benbow and family, Mrs. Fieldhouse, Miss Chapman, Miss Campbell. We understand the "Lady Bird" is likely to make Timaru a regular port of call. She sailed again about noon. Press, 10 Sept. 1863: There was no room to doubt that the fever which raged last summer was brought by the Huntress. Fever had never been known here before, and in many instances it had been traced to servants engaged from that ship. To prevent spread of disease from subsequent ships arriving, strict quarantine regulations were put in place. Now immigrants are landed in Camp Bay, and now under canvas, however portable houses were ordered, and erected. It was thought had these regulations been put in force on the arrival of the Mary Ann, Mystery, and Huntress, much expense would have been spared to the Government. The immigrants by those vessels had cost the Government more since their arrival than the expense of bringing them here. From notes of cases which had come under notice whole families had become affected with & severe form of fever from having engaged servants from these vessels. This would not have been the case if the immigrants had been prevented landing. Press, 11 Dec 1863     To conform to the Data Protection Act

all pages have been altered to exclude details for living people other than the

name. Images and data used in this site copyright.

|