The

Ag-Lab in England - 1750/1860

75%

of England's population were employed as farm

labourers in England where only 6% of the male

population could vote.

The hierarchical system was three-tiered - 1. The landlord: most of the land was owned

by the gentry; 2. The farmer: he rented the land from the gentry;,

and 3. the landless labourer, a peasant, who did the work.

The

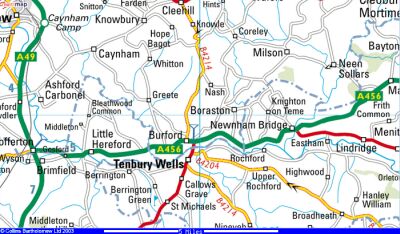

villages where Benbow family forbears lived are located primarily in southeast.

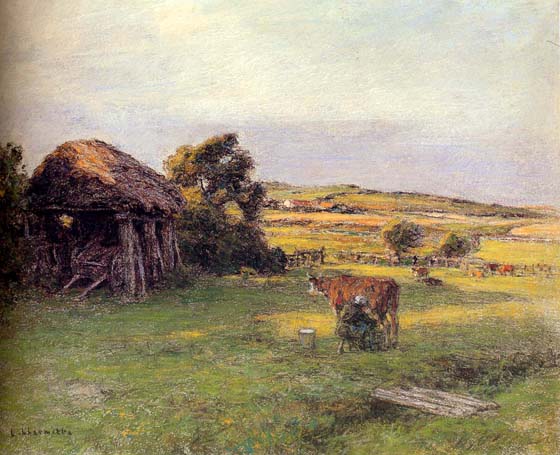

"Shropshire is in west midland England and was also known as Salop -a

large county with a small population mostly in villages. The River Severn

divides Shropshire equally into northeast and southwest halves and

separates the rolling acres of fertile agriculture lands in the north and

east from the less fertile majestic hills of the south and west. The

countryside has farms, herds of sheep, grazing cattle, cottages, grain

fields and many trees (Description from Pigots Directory of

Shropshire, 1842)

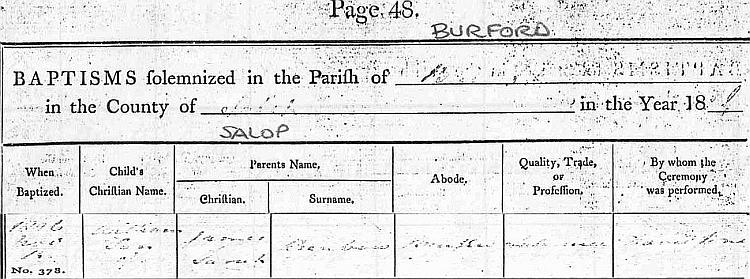

Burford in the Diocese of Hereford where William Benbow

was born is a parish in the extreme south of Shropshire, and divided from

Worcestershire by the River Teme (the boundaries changed aft. 1823 so Wm's

father was born in Worcestershire 1793)

Burford is divided into eight Townships: Boraston, Nash,

Tilsop, Weston, Wetmore (or Oughtmore), Whitton (the township is on the

northern extremity of Burford Parish, and takes its name from the

Whittons, its early owners in the 12th century) and Greet. The Parish area

is 6,672 acres, and in 1861 it's population was 1,121.

We have no record of how our Benbow ancestors lived

in the 1700's but if a small-holder, life was bearable. They

would have been able to farm on "common land" leased from it's

wealthy proprietor who owned large areas in the district. The

land was divided in long narrow strips however farms were passed down

to family members and it's area grew smaller with succeeding

generations. The common land allowed peasants to grow their own

vegetables, raise and graze their animals and to gather fuel for their

fires, but if the harvest was smaller than usual or if any other

unexpected losses had happened, winter could be cold, long and a

hungry time eking out the food and other supplies stored over the

year.

In the 1700's, the farm labourer's house was one room on the first floor and one room above it -no sanitation, no water, poor hygiene and bathing was infrequent and a luxury. Leonard Thompson remembers, �But all the boys and young men swam naked in the river in the summertime. It was our biggest happiness. Boys were washed until they were about two, then their bodies didn�t see water again until they learned to swim. We didn�t look dirty.� When they did bath, the water was cold. All transportation was on foot. Today thatched cottages

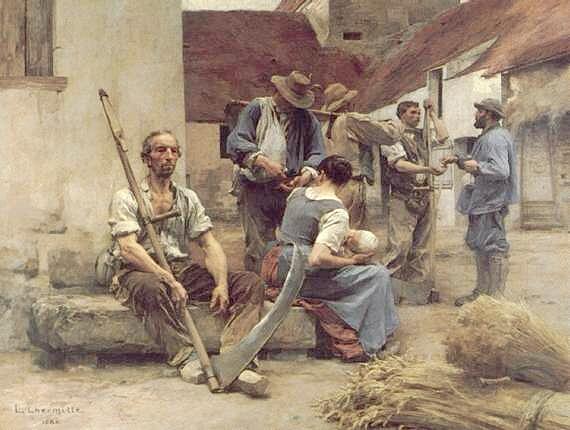

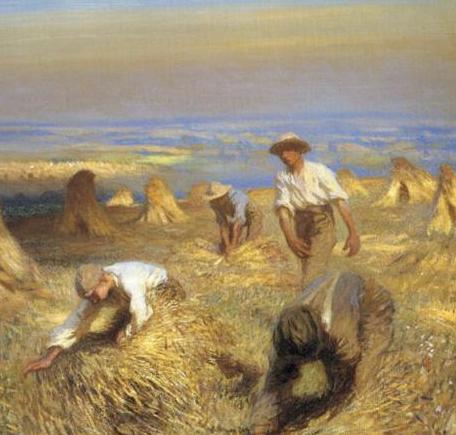

are considered "quaint" but the thatched homes of the 1800's were

not inviting. The wealthiest rural poor lived in a four-room Agricultural unskilled labourers who did not own land worked for a �farmer� and were the lowest class in rural English society. At that time, there was a huge emphasis on class distinction - you married within your "class". The wealthy landowner had servants - the more they had, the more they gained status in society to display their wealth. It was common for farmers to have servant girls - they cost less and a male servant was taxed. However, a male servant gave one much more status. Besides the domestic servants, there were coachmen (who maintained and drove the carriage) the groom (who took care of the horses) gardeners and gamekeepers (to protect the game - rabbits, pheasants, etc. from poaching. A maid working from 6am to 11pm at night, received just �11 to �14 per year. The principal land use was growing grain or raising sheep for wool - both required a lot of manual labour. Farming tools were common, but until machines were invented, animals were raised for food, but until ploughs were invented, not used extensively for cultivating the land. Rural life depended on good weather in the summer resulting in a good crop as a long winter meant hunger and discomfort. People rose with the sun and went to bed when darkness fell. Farms were ploughed in the late autumn or winter and wheat (the most common and profitable crop) barley, and oats were planted - these grains were collectively referred to as �corn�. (Corn ie today's maize, did not exist in England.) Sheep were grazed throughout the field to fertilize the crops and after cultivation, the soil was �harrowed� to break it into smaller chunks. Wheat was cut with the sickle, or an old-fashioned cradle and then carried to the barn. A team of five men working all day would harvest about two acres using a small sickle at the beginning of the 1800's -a scythe was used in the second half of the century. (There were just three holidays: Good Friday, Shrove Tuesday, and Christmas Day)

Jobs which were almost exclusively done by adult male workers were the care of farm animals, milking cows, feeding pigs, herding and shearing sheep and looking after the poultry along with trimming and layering hedges and maintaining the farm buildings, fences, gates, farm tracks, ditches and ponds, carting, cutting wood and making faggots; the reaping and weeding were done by both men and women. Before enclosure, a cottager with a pig or two, a cow and some poultry on the common had the right to gather firewood and could maintain a certain measure of economic independence however by 1800, new methods of agriculture machinery were developed and Shropshire recognised land use would be more efficient in larger plots so enclosure ie "the process of inclosing (with fences, ditches, hedges, or other barriers) land formerly subject to common rights" (inclosure) occurred. Prior to enclosure, there were common areas that belonged to everyone and here peasants could gather wood and grow a few crops. It was returned to the control of the landowners and redistributed and was no longer available for the poor to use. Scavenging on someone else's land became illegal, and small farmers (who had no political influence and were generally given the poorer plots) often lost access to wood and water and this increased hardship for the rural poor (Enclosure Acts).The process was not standardized until the General Enclosure Act of 1801 (Inclosure), when enclosure became common and forced many peasants to move to the city in the hope of finding new work. After enclosure he became a dependent wage labourer. Squires and farmers prospered as never

before but the labourers' share of the wealth which

they had toiled to create, increased very little. James and Sarah Benbow moved after 1823 from Rochford to work at Weston Farm for a farmer who owned or rented several cottages or houses where his workers and their family lived. The cottage may have been free or leased at a small rent to them and a small vegetable garden could be planted nearby for own use. This allowed a family to continue to live in the same cottage for more than one generation and made for a stronger relationship between the farmer and his workers. Labourers' children were encouraged to begin farm work 'as young as possible' (about 10 years old) However, the farmer had no legal obligation to the labourer and could drive the family out of the cottage at any time. Education: In 1811, some members of the Church of England became appalled that lower-class children could not read the Bible. They started Sunday Schools first. These gradually became weekday elementary schools and by 1839, became so popular that these Church of England schools were supported with public funds. This was the only way the poor got a higher education in England in the 19th century. By 1862, the government required standards. Boys and girls were required by the end of the �sixth standard� (tested) to read and write simple passages and to do arithmetic. However as late as 1871, more than 19% of men and 26% of women getting married still could only make an X next to their name in the parish register.

In 1826, William Benbow was likely born in his parent's tied cottage on Weston farm where they were working and he was baptised in nearby Burford. The Burford baptism registers are deposited at the Shropshire County Record Office, The Shirehall, Abbey Forgate, Shrewsbury and contain this faded baptism entry of William, son of James and Sarah Benbow, abode Burford, labourer on 15th November, 1826. Ceremony performed by David Jones. Burford is right on the boundary with Worcestershire (Tenbury Wells) and close to Herefordshire. He grew up on the farm and by age 10 did jobs suitable for children such as scaring birds from crops advancing to more skilled jobs as he grew older. 1830 meant with increased mechanisation and the Industrial revolution, the introduction of the seed drill and threshing machines took away valuable work from the labourers, and worse still, replaced them and labourers left England or moved to the cities to find employment. 'Swing' riots broke out in the southern counties of England, areas most affected by enclosure. The rioters were demanding a minimum wage, the end of rural unemployment, and tithe and rent reductions. The riots took the form of machine breaking (the hated threshing machines), arson, meetings and general unrest. These riots were the first demonstration of agricultural unrest and this unrest continued particularly after the passing of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. William would have attended a hiring fair to find

work. (Wikipedia: Prospective workers would gather in the street or market

place, often sporting some sort of badge or tool to denote their

speciality, shepherds held a crook or a tuft of wool, cowmen brought wisps

of straw, dairymaids carried a milking stool or pail and housemaids held

brooms or mops, this is why some hiring fairs were known as mop fairs.

Employers would look them over and, if they were thought fit, hire them

for the coming year, handing over a shilling to seal the arrangement. Both

male and female agricultural servants would gather in order to bargain

with prospective employers and, hopefully, secure a position. The yearly

hiring included board and lodging for single employees for the whole year

with wages being paid at the end of the year's

service.

1841 census;

William is now aged 14 was hired as a farm servant by widow

Eleanor Mason and her 2 sons at Tenbury for a period one year.

This meant he 'lived in' on the farm and shared the family table at

meal times. Other casual labourers from the neighbourhood would be

hired to supplement their work in busy periods. Travelling to the hiring

fair and from there to a farm, explains the sometimes surprising

mobility of some ag-lab ancestors. Once at the farm a worker might meet

and fall in love with a farm servant from another village and decide to

get married. If married, farm servants were obliged to live out and had to

find lodgings in the surrounding villages. Before

1834 poor relief was dealt with at parish level. It had its basis in the

early 17th century when it had been introduced as a way to alleviate

distress and to ensure public order. It was up to poor law guardians to

decide who was eligible for help, and as they often knew the recipients,

it could be a fair system. Labourers could ask for 'outdoor' relief to

supplement their loss of wages due to illness or unemployment. The Poor

Law Amendment Act of 1834 aimed to do away with outdoor relief and make

the workhouse the only way of accessing help. It was hoped that this would

act as a deterrent and make sure that only the genuinely destitute would

apply. A FAMILY BUDGET reported in 1843 gave an example of a weekly family budget:

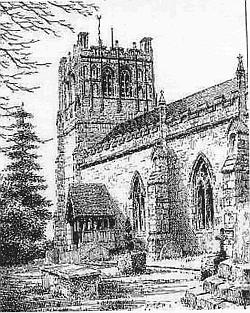

The romantic family story that William found work as a head gardener at Ludlow Castle where he met Mary Postem and eloped is highly unlikely but very romantic! Never-the-less, on September 3rd, 10th and 17th 1848 the Banns for the marriage of William and Mary Postens were called at St Mary's Church, Burford where the marriage took place on November 20th 1848 The couple were described as "Full age' which was the usual description used if both parties were over 21 when they were married. Witness to marriage - James Benbow (William's brother) and Mary Hill. All signed with a X. The Marriage Registers for Burford St Marys were still in the custody of the Vicar of the Burford Rectory, Tenbury Wells, Worcester in 1980. After

marriage William and Mary were able to rent a tied cottage

next door to parents James and Sarah. Here their family - Ann 1849,

John 1851, James 1854, Sarah 1855, Elizabeth 1859 and William in 1861,

were born.

1851 Census: (Incorrect

Spelling "Benbham") Reg. district: Tenbury; Household

Members: 1861 Census:

Weston cottage: (daughter Ann not listed as here

so may have been employed)

William Benbow; Head; Married; M

34 yrs; Labourer b Burford, Shropshire

Mary Benbow: Wife; Married; F 33

yrs; b: Stanton Lacy, Shropshire

John Benbow: Son; M 10

Scholar yrs; b: Whitton Burford, Shropshire

James Benbow: Son; M 7

Scholar yrs;b: Whitton Burford,

Shropshire

Sarah Benbow: Daughter; F

5 yrs;b: Whitton, Shropshire

Elizabeth Benbow: Daughter;

F 2 yrs;b: Whitton, Shropshire

Next door: Weston cottage: (William's parents) James M 68 yrs (he died abt 1868 at Oswestry, Tenbury) labourer b: Herefordshire and wife Sarah nee Porter) F 63; b; Worcestershire and brothers James and Jonathan (WHITTON is a parish of Burford. 12 houses, 68 inhabitants. Four-and-half miles south-east of Ludlow. (1824 Gregory's Gazetteer of Shropshire) The women and

daughters would have worked in the dairy, vegetable plots or in the house.

Their lives may have seemed secure but they were at the mercy of

their employer who could, without any notice, lower their wages or even

turn them out of their cottages if they felt they could no longer afford

to employ them or if they had become too old or too sick to

work.

The average farm labourer had one cooked meal per week - they did not have ovens. There was likely a small garden in which they would grow vegetables, keep chickens, or even raise a pig. Bread, milk, cheese, eggs, and beer were staple foods. They almost never had meat, sugar, or tea. Cheese and bacon were favourite and rare foods for the poor and Pudding which contained blood and spice and smoked well to give it a strong taste was a favourite lower class dish. Bread was baked in an oven built of brick with an iron door at the community bake house. The bake house had a grate at the bottom and wood was burned below to get the oven hot. After it came to temperature, the bread dough was placed on top of the grate. When the bread was baked, the ashes were picked out of it. Boiling food was more common than baking it. Leonard Thompson, a farm labourer, recalled that, �One of our great desires was to have cake. Nearly all our food was boiled on account of there being no oven in most of the cottages. A �treat� was any party where you could eat cake. Drinking water was obtained from a well or stream and brought to the cottage in pots. Water pumps replaced wells in the early 1800's however it was often contaminated so people drank tea and beer instead. Beer was provided free to the labourers working in the fields. Stopping at �sevensies, ninesies, elevensies, dinner and foursies� it was recorded they would drink a pint of home-brewed beer at each stop. If a labourer wanted to drink after work, he went to the pub. ��the pub was distinctly disreputable and disapproved of, not only because it was the resort of the poor, but because it led them out of the peculiarly straight and narrow way that was all that Victorian respectability permitted them. As the century wore on the condition of our agricultural labourer ancestors and the way they were perceived by the more fortunate parts of the population deteriorated. They were badly paid and their 'cottages' were often small and in a sorry state of repair. They were seen as idle, unskilled and unintelligent, however the range of farm work that these 'unskilled' people were expected to undertake, shows just how little the perceived view of the time was justified. The death occurred of oldest son John Benbow in 1862 and William and Mary decided to immigrate the following year to New Zealand in the hope of forming a new life.     To conform to the Data Protection Act

all pages have been altered to exclude details for living people other than the

name. Images and data used in this site copyright.

|

cottage with a roof and walls

that leaked water allowing dirt and bird droppings to ooze below. Many had

floors of earth, often damp or they were covered with crushed rock,

called "clutch" Sometimes bricks were laid over the clutch.

cottage with a roof and walls

that leaked water allowing dirt and bird droppings to ooze below. Many had

floors of earth, often damp or they were covered with crushed rock,

called "clutch" Sometimes bricks were laid over the clutch. Wives of the

harvesters were employed to rake the cut corn into rows ready to be

tied into sheaves and numbers of women, boys, and girls worked at various

tasks and were paid much less than adult males. They were allowed to

glean the fields for grain for own use after a harvest - it was not until

The Agricultural Children's Act of 1875 had prevented children under ten

from working in the fields. In winter, the wheat was threshed by walking

in a circle and beating the wheat with the �flail� until the grain

separated from the chaff or straw. After �winnowing� (sifted to

separate the grain from the chaff or straw) it was placed into bags

and taken to the mill to be ground into flour for breadmaking.

(Threshing machines were not invented until at the beginning of the

1800's)

Wives of the

harvesters were employed to rake the cut corn into rows ready to be

tied into sheaves and numbers of women, boys, and girls worked at various

tasks and were paid much less than adult males. They were allowed to

glean the fields for grain for own use after a harvest - it was not until

The Agricultural Children's Act of 1875 had prevented children under ten

from working in the fields. In winter, the wheat was threshed by walking

in a circle and beating the wheat with the �flail� until the grain

separated from the chaff or straw. After �winnowing� (sifted to

separate the grain from the chaff or straw) it was placed into bags

and taken to the mill to be ground into flour for breadmaking.

(Threshing machines were not invented until at the beginning of the

1800's)