50th Queen's Own Regiment embarked from Sydney for India the month of February 1841 in two ships, the Lady

McNaughton and Crusader, arriving at Calcutta on the 19th April 1841.

We were sent to a station called Chinsurah, 22 miles

from Calcutta, a most unhealthy place on the banks of the

Hoogly River. The Regiment had no sooner landed than the men

were attacked by cholera, which struck terror into the men,

as they had been healthy in Australia, with scarcely a man in

hospital. A man would be taken suddenly ill with cholera in

evening, sent to hospital and be dead and buried by six or

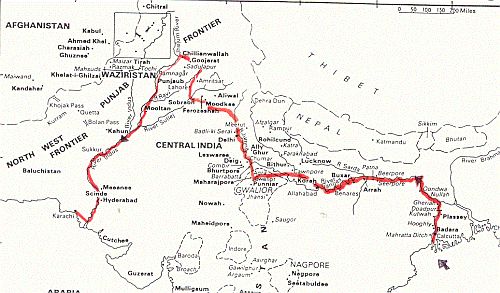

seven the next morning. However, the Regiment was ordered to Fort William, Calcutta, and there the cholera was nearly as bad, men being taken to the hospital at Kederepore, and never saw the Regiment again, being dead and buried or invalided home. At length the Regiment was ordered to Moulmain, as it was expected we should go to war with Burmah. The Regiment sailed in three vessels, two sailing ships and one steamer. Of course, we expected the sea air would have rid us of the plague, but when the steamer passed us on the passage she reported having eight men lying dead on her decks. At last we arrived at Moulmain, and went into camp. It was an old burying ground, that was used by the General Hospital in the war time of 1824-25-26, so I concluded there was a good number of deaths in the three years' war, for on a dark night you would go into a hole up to your body, and you were very lucky if you did not get a sting of a Scorpion or Centipede or the bite of a snake. However, there was not to be any war with Burmah, and we were shifted back again to that Golgotha Chinsurah, where we had another attack of cholera. A small incident occurred to myself one day. The men were ordered to receive their pay every day at 12 noon. An Officer was to be present at the payments. I had felt myself rather queer in the morning, and I went to the hospital to get a dose of medicine which I got and it made me feel queerer. Pay time came and I was called. The Captain looked at me, and said, 'Pelvin, you don't look well.' I told him what I had done, and he said, 'You must go back to the hospital. I said I was all right. The Captain called a Corporal and two men and ordered them to take me to Hospital at once, whether I liked it or not, and the doctor kept me in hospital for three days. That was the first and last time I was in the hospital, for many years. Our next shift was to that renowned place, Cawnpore. In those days (1842) locomotion was not so far advanced as at present. We were to go by native boats a distance of 600 miles, and all against the stream. Our progress, you may be sure, was very slow, as the Hoogly and the Ganges are very rapid rivers, but such a sight you never saw. There were upward of 100 boats to take one Regiment. There was Officers' Budgerous barges, the Hospital boats, Men's boats, Cooking boats, Store boats, all sorts and sizes, but not one with a keel to it. They all had either round or flat bottoms, and if caught in a gale over they must go. An incident of this sort occurred to us between Benares and Patna. This Great Fleet was plodding along at a snail's pace one day, when a gust of wind caught a mat sail, and tumbled the boat over with a number of soldiers in it. Some tried to swim, but got exhausted and were drowned. Others stuck to the boat, and after going many miles down the river got saved by the boat grounding. The boat I belonged to happened to be behind the Fleet, and we picked up several, who told us that many native boats passed them and would not pick them up as they worship the Ganges. The boats always stopped at night, fastened to the banks of the river by posts and ropes, off again the next morning, and the current was very strong, would make but very little headway by night as you could see the place you used the night before. It took the Regiment months by this sort of travelling to travel 600 miles. We passed by Dinapour, Benares, Allahabad, and other small towns en route. Having arrived at Cawnpore, then an Independent Kingdom, we remained in Barracks until the War broke out with Gwalior, a small Independent State. The army was divided into two parts, or wings. The right wing was commanded by Sir Hugh Gough, Commander in Chief, the left wing was commanded by Major General Sir John Grey. We remained in camp at a place called Duboy, in the Bundelkhand, a district on the Frontiers of Gwalior. On the 29 December 1843, the right wing, under orders of the Commander in Chief, attacked the Maharattas at the village called Maharajpore, the Governor-General, Lord Ellenborough, being present. The enemy stood their ground well, but was forced to retire with the whole of their cannon taken, and made for the jungle.

On the same day, December 29, 1843, General Grey

attacked with the left wing the village of Punniar, above the

Maharattas, who were 13,000 strong with a good strong

artillery force. After fighting desperately they abandoned

the whole of their cannon taken and their army scattered.

1st Irish were allowed to have a contingent, which made us

pay dearly for it during the mutiny of 1858, as they drove

their Rajah off his throne, and he had to fly to the British

for protection, and his army joined the mutineers. Lord Ellenborough was so proud of the gallantry displayed by the troops at Maharajpour that he recommended to the Imperial Government at Home to have a Star of Bronze made from the enemy's captured guns for the army of Gwalior, one of which I have the honour of wearing. Lord Ellenborough did not remain Governor General of India long after this as he was superseded by Lieut. General Sir Henry Harding sent out in his place. After this the troops returned to their respective stations and we went to Cawnpore, also the 9th Lancers and 40th Foot with 16th Lancers to Murat, 3rd Buffs to Agra and 39th to Allahabad. Lord Ellenborough was a great man with the Army and I believe would have made a good General. Having a relation in the 16th Queen's Lancers,(Richard did not state who this was - it was his brother James Pelvin who d: 1849 and was bur: at Unballa) I had been trying for a long time to get to that regiment, but our Colonel would not let me be transferred on account of the regiment being so much under its strength. However, in 1844, we had several strong drafts of recruits from Home, and I again applied for transfer, which the Colonel sanctioned and I was transferred to the 16th Lancers at Meerut on the 1st July 1844, remaining with my oId regiment until an opportunity should occur of joining my new one in a few months. It occurred when a Corporal of the 40th regiment came to Cawnpore with a prisoner, and I had the chance to join my new regiment, which was 300 miles up and 900 miles from Calcutta. Having joined by new Regiment, I was very much struck with the relaxed state of discipline in the cavalry regiment, but they were a fine body of men, men generally speaking of good education, and what you may call devil-may-care sort of fellows, full of life but very fond of the soldiers' canteen, which got many of them into trouble. I will give you an instance of one; it was a man of good birth and education. His name was Charles Percival. He was in Christchurch when I arrived in this country (NZ). Perhaps some of the old identities knew him, as he had a brother or cousin who had a sheep station in the McKenzie Country. Charley took up the profession of a Military Lawyer - the worst profession any many could undertake - always getting into trouble and always under some minor punishment. But one good thing he did for his comrades, and the regiment in general. At one half-yearly inspection by the General of the District, the men are always asked if they had any complaints to make. My bold Charley stepped out and said he had. "What is it, Percival?" says the General. He (Percival) made a claim for sashes, cap lines, boot straps and etc, that had not been issued to the men for two or three years. The (Colonel Caseton?) was asked what sort of a character Percival had; and you can rely upon it Charley did not get the best.. The General said, "Now Percival, I am bound to forward your claim to the Horse Guards and if it is false or not true, I will have you tried by General Court Martial." In course of time, an order came from Horse Guards that all men of the 16th Lancers to be paid compensation for all necessaries that had not been issued to them, so Charley got off with flying colours. He lived to go through the Sutlej Campaign when the Regiment broke up in 1846 and I volunteered to the 3rd Kings Own Light Dragoons. When the 16th arrived at Portsmouth a carriage and pair drove up to the barracks and took Charley home. I heard no more account of him until I came to New Zealand when a man living in Timaru, of the name of Manning, from Christchurch told me he knew him well, and his parents sent him out here with 7,000, which he ran through, got another 7,000 from Home and squandered that the same as the first. The Rev G. Parson Foster knew him well, and he told me that Charley Percival did not know the value of money.

The 16th Lancers remained at Merrut until the end of

December 1845, when the war broke out, the Sikhs of the

Punjab, crossing the river Sutlej, and attacking our army at

Moodkee, while the troops were cooking their dinner. Of

course, the troops got under arms at once, but our force was

very small in comparison. Under command of Under Major-

General Sir John Little, with only 5000 men and 21 guns, when

they gave them a complete check; and sent them back to their

entrenched camps at Ferozeshah The garrison from Umballa not

having reached the front. The Sikhs at Ferozeshah made a great stand. The Meerut division was ordered up to the front by forced marches and at four o'clock on the afternoon of 21 December 1845, Lord Gough, with 16,700 men with 64 guns advanced to the attack of the Sikhs' formidable entrenched camps. Daylight having near gone, both armies lay on their arms all night. Lieutenant- General Sir Henry Harding took the command. He was Governor- General of India at the time - a gallant soldier.

In this engagement we lost 694 killed and wounded,

1721. Prince Waldman of Prussia was in this engagement. I

was not in these two engagements as the 16th Lancers, which

was with the Meerut Divisions, did not get up in time. The

Sikhs lost 67 pieces of cannon at Ferozeshah, and 17 guns at

Moodkee. On the march, we went by forced marches. The day we reached Loodiana was a most terrible march. The Infantry was complete exhausted, and the Cavalry were tired sitting in the saddle. We had been marching from 2 o'clock in the morning when the troops came to Budiwall (or Budiwah) about three or four o'clock in the afternoon. A force of Sikhs was in Budiwall, but our force, being so fatigued that he dare not attack them, and we had to make a long detour to get clear of their fire. The Cavalry had to make feints to clear their fire on us. The consequence, the Infantry got round and the poor recruits and women and children were so exhausted that numbers of them lay down on the dry plain and were taken prisoner. When we got clear of the enemy, all those that could not proceed, the Cavalry dismounted their horses and put them on their horses, and led the horses until we came to the camping ground. I dismounted and put a very young recruit into the saddle, and led the horse. I must give the Sikhs great credit for their humanity, for when the war was all over the whole of the men, women and children were returned without being ill-treated.

Our next little game was to settle with the Budiwall

Sikhs after delivering food and we stopped in camp for two or

three days. In the meantime they shifted their quarters to

the village of Aliwal, between Loodiana and our camp and near

the Sutlej river.

On January 28th 1846, Sir Harry Smith moved down to

attack the Sikhs. It was a beautiful morning, and about 2

o'clock we came in sight of their camp and the plain was

level as a bowling green, but there were deep watercourses or

nullahs running through the plains Before we got in reach of

their fire their guns opened upon us, and it was a curious

sight to see the Infantry all lying flat down when they came

within reach of their cannon, while the Cavalry had to sit

still and receive their fire, having a man knocked over here

and another there and a horse here and there. At last we

were ordered to advance but still keeping in line with the

Infantry on the left flank to prevent the enemy from

outflanking us. At last we came to a tope of trees, which a squadron was ordered to clear and it was full of the enemy, - a very bad place for Cavalry to act in, as we could not act together. We routed them all out after some desperate fighting, and we dare not follow them up. We had to return and take our place on the left of the line. We lost about a dozen men in that affair, but the enemy paid for it dearly. The Infantry and Horse Cavalry charged the village of Aliwal, and completely routed them, taking 52 guns, and we followed them up arid the Horse Artillery and Cavalry also the taking of their camp. We also took a European, an East Indian Company Horse Artilleryman, who had deserted some years before. He was made a prisoner and brought before Sir Harry Smith and sent under a guard to one of the regiments, but what became of him I don't know. My poor rear rank man, Ben Smally, was shot in the chest, a nice quiet Yorkshire man, and died in the General hospital and the Army marched back to Sobraon. The Commander-in-Chief having received his heavy guns from Delhi, attacked the Sikhs' entrenched camps at daylight on 10th February 1846 and cut away the centre of their bridge of boats across the Sutlej River, one of the strongest rivers in India, the current running something like in the Waitaki River here. Of course the enemy's retreat was completely cut off which made them thoroughly desperate and they fought with desperation. They were the best troops in the enemy's army. The Kahlsa troops fully thirty thousand strong with 70 pieces of cannon, with a reserve on the opposite side of the river and as there was a ford lower down it was expected that the enemy would cross the river at this ford, and come to the assistance of their Army when attacked by us if required. Our Brigade of Cavalry with a battery of Horse Artillery, was ordered down to this ford. They unlimbered their guns and sent us a few shots across, which dropped short. They ceased firing and remained watching us until Sobraon was taken, but these same troops made us pay dearly for it at Chillianwalah, in the campaign of 1848 and 1849.

Now to return to Sobraon.: - Mind you, these troops

were not common native soldiers, they were disciplined French

Officers, and had their Bands and Officers and colours the

same as any European regiment and as brave soldiers as any

men in the world, which they proved in the campaign of 1848

and 1849. When the campaign of 1845 and 1846 broke out, the European Officers all retired from the Sikh service. Only the officers' names I can remember are Generals Ventura and General Avitable and entered our service after this war. I believe the taking of Sobraon one of the greatest battles ever fought in India and with the greatest loss of life to the enemy and terrible heavy to the British troops. Sobraon. As I said before, the action commenced at daybreak on the morning of the 10th February 1846, and was ended about 11 a.m. The total loss of the British was: killed, 1320; and wounded, 2063. The Sikhs, in their efforts to cross the bridge of boats that was cut away, hundreds upon them was drowned in the river, swimming to get to the bank on the other side, and I believe the Sikhs themselves owned to the loss of 14,000 men.  I went down to the entrenchment camp after the action was over, and such a sight I never anticipated, but once seen at Chillianwallah. Men were blown up with rockets bombs, shells, grape and shrapnel and almost any projectile you can mention. I may say thousands upon thousands were driven into the river like a large flock of sheep. The sight was awful, yet the Sikhs were that brave they would not surrender or put up a flag of peace, but would prefer death. And they are now at the present with the Gourkas,the bravest and most reliable native soldiers we have in British India, and as good or better than some European nations.  Well we crossed the Sutlej the day after the fight, into the Punjab, and made for their capital, Lahore, when the Ranee or Queen Mother sent to implore the forgiveness of the British, by Golab Sing Rajah of Junmu and Cashmere, so peace was proclaimed. (So the political I leave to the politicians.) And that is how our army went into Standing Camp while the 16th Lancers, were ordered Home, after 25 years' service in India. A Cavalry Regiment in India being double the strength of a Cavalry Regiment at Home, being 700 strong,of course we should have a greater number of men to spare, the consequence the men are allowed to volunteer to any Cavalry Regiment in want of men, and each man receives a small bounty at the volunteering time. I made up my mind I would volunteer, so I joined the 3rd King's Own Light Dragoons, and had another seven years in India. So the standing camp was broken up, and the Army went to their respective stations. I went to Amballah with my new Regiment, and there settled down to garr~son duty and barrack drill. Having a large number of young horses to break in we had plenty of riding school. The 3rd King's Own Light Dragoons remained at Amballah during 1846, 1847 and part of 1848, when our second campaign took place when Runjeet Sing was living,the only man that could command the Sikhs and keep the Punjab in order was dead. The Sikhs' chiefs and army still considered themselves invincible. As we had had some very serious losses in Afghaniston, they thought very little of our valour, and treated us with contempt, which they let us see in the second campaign, to their grief. While we were at Amballah in cantonements, a force from Bombay, which was under command of General Whish, a gallant regiment of ours came from Poonah to replace the 16th Lancers which had gone Home. They laid in the same cantonement with us, and had one half of our barracks at Amballah. This regiment had never been under fire or on a campaign since the Peninsula war. Of course, the men would boast very much of what they would do, and what they would not do (and they were not going "to take medals for picking off black men) in case they had an opportunity of meeting the enemy in the field. We had no idea that we were going to make another campaign into the Punjab at this time. All went very smoothly until the second campaign opened, and of course this gallant regiment of cavalry was real hot to meet the enemy. They were in General Pope's Brigade, and we will leave them there for the present.

Well, the campaign broke out again in 1848 on 2nd

December. The Sikh's cavalry advanced to the front, and this cavalry brigade of ours asked permission to be allowed to charge. the Sikhs cavalry. They got it and did charge splendidly. The Sikhs' cavalry turned about, and Pope's Brigade after them until they came on the infantry under the sandhills. The infantry opened upon them a most destructive fire which killed a number of our cavalry officers, men and horses. The enemy eventually took to flight and crossed the river to their army and Pope's brigade returned but their Colonel was killed, also Brigadier General Cureton and his youngest son and other that I do not remember. So that was a lesson they did not forget for a long time. They adored their colonel, and Brigadier-General Cureton who had commanded the 16th Lancers for many, years. His youngest son was deeply regretted. Our next move was to cross the river Chenab by a ford lower down the river and try to outflank them. Our brigades, and some batteries of horse artillery and some brigades of infantry crossed to the other side, and when the enemy saw what we were up to, they struck camp and marched off, and the main army crossed over, and our outflanking party met them, and we joined the main force again. (This action is not recorded.) The enemy then made for the jungle at Chillianwallah, where they pitched ,their camp and where Sir Hugh Gough made a very grave mistake. It occurred in this way. The Commander- in-Chief was out reconnoitring with his staff, when a shot from one of the enemy's guns fell in amongst him and his staff. This got the old Tipperary man's blood up. He at once ordered the army to advance - they did so but a more miserable country could not be imagined., a nasty place with trees about 20 or 30 feet high, with thorns as long as your finger. The horses (all entires) forced and forced their way amongst the trees, biting and crushing each other enough to take a man out of his saddle. Our position was again on the extreme left of our army and the right of the enemy, where they had a battery of artillery firing on our regiment, and we had to' move our position which is a position not to be envied by anyone, as we could not see them, but only the flash of their guns. There we sat still in our saddles like statues, as a target to be fired at. The men grumbling at not being allowed to move. The consequence was that presently a shot came from their battery, and struck me right in the centre of my shako, so suddenly and made such a hollow sound, having cut the strong of the lining away, that the shako came over my eyes, and of course I could not see for a time. I accused my right hand man for knocking my shako down over my eyes with the back or flat of his sword. Of course he denied it, and told me to take off my shako and look at it. I did so, and to my astonishment a nine pound shot had cut the crown out of the number plate. (You may ask what I did with it, well I just threw it away, and put on my forage cap.) Shortly afterwards we were ordered to take ground to the right. Another shot came into the regiment from the same battery and went through three horses and they dropped like a shot as they saying is, without injuring any of the riders. The riders, of course, made to join the infantry, as a cavalryman is not much without his horse. Being isolated and on foot this troublesome battery at last got its desserts. The grey squadron on foot was ordered to make a detour around to the extreme right of the enemy, and attack their guns. They got round, and charged them, drove the enemy from them and spiked the whole of them - that is they put a jagged spike in the touch-hole, which cannot be withdrawn.

On the other part of the line, the action was far more

serious. The whole line advanced. I think I had better

refer to history for the remainder of the action, as a

soldier in action has enough to attend to the orders he

receives in such an action as this was, where you could not

see 50 yards in front of you, as was the case at

Chillianwallah. Lord Harding, in his dispatch relating to this action, charged Lord Gough with indiscretion of the most serious character, in attacking the enemy when the day was far spent, the troops wearied, and no time to make preparation to avoid unnecessary loss, without any reconnaissance, and added to, "his indiscretion cost us dear." Had the result been otherwise, Lord Gough would have been praised for the dash he displayed in attacking the Sikhs, and in spite of all the above-named disadvantages, for having routed them utterly. The fact is, he came on them rather suddenly, and Lord Harding suggests that the Irish blood of the old soldier was irritated by the fire from their artillery as he was reconnoitring. Gough opened a cannonade which lasted an hour and a half, then moved his left 3rd and 4th Brigade to flank the enemy. In doing so it was terribly mauled by the enemy from concealed batteries, and when the troops got up to the guns they retired rapidly. The 5th Brigade under Mountain, carried the guns in their fronts, but the Sikhs' infantry opened such a fire of musketry on their flank and rear that they too retreated in haste, but in good order. On the extreme right Godby's Brigade were received with equal firmness, and outflanked and attacked in the rear by the Sikhs. In the melee the 2nd European East Indian Company especially distinguished themselves by charging, rear and in front, and checking the enemy, but the cavalry on the extreme right, under Brigadier Pope, being ordered to charge, the enemy's horses, faced about and left the field (with the exception of a party of the 9th Lancers, who were rallied.) This is an error. The 9th Lancers were not in Pope's Brigade. I have been in several engagements with the 9th Lancers and in several actions and they never retreated before an enemy. It was another regiment that was in Pope's. I am sorry to say that I am not at liberty to expose them, as being a pensioner, I may get into trouble over it. The runaways made right for the three troops of Horse Artillery, which had been placed in support in their rear, dashed right through them, upsetting waggons and horses, and scurrying through the hospital tents,pulled up exhausted and discredited, leaving the field of battle far behind.This panic, so unaccountable and unusual, a serious loss for the Sikhs captured the guns, two of which only were retaken, and cut down 70 gunners. The British, however, remained masters of the field, but 26 officers and 731 rank and file of the European troops were killed; 66 officers and 1146 were wounded. Four of our guns and five stands of colours. The Sikhs might well have claimed a victory, which they did, for, after the action was over, they fired a Royal Salute of 21 guns. The Sikhs resolved to march off at night, taking with them the guns, thus ending the battle of Chillianwallah, with what a sacrifice of life. Allow me to give a bit of advice to those who advocate war, and come with me over the battlefield the next morning and I believe it will cool their ardour for wars. My regiment, the 3rd Light Dragoons, was ordered out with a battery of horse artillery to reconnoitre. We went through the ground the battle was fought the day before, and such a sight I am sure they would never forget till their dying day - soldiers lying dead in all directions and in all positions, some at full length on the ground face downwards, others on-their backs, others with their knees drawn up and hands clenched together in mortal agony at their last gasp. Many of these men and officers I have no doubt would have been saved if we had had daylight, but it was coming dark. To give an instance of the severity of this action - the First Battalion of the 24th Regiment that went into action 1300 strong, they had 13 officers killed and 500 rank and file killed and wounded. Colonel Pennycuick and his son and 11 other officers were killed at the same time. The other regiments, both European and native, in proportion. I hope to God that the inhabitants of New Zealand may never see such a destruction of life, although I do not believe in peace at any price and if I was young again, I might be induced to join the army again, although it is now nearly 40 years since I left the regulars. So much for the Battle of Chillianwallah, one of the hardest battles that has ever been fought in India and under the most disadvantageous circumstances. When the news of this action reached England there was a loud outcry against Lord Gough, and a demand, almost unanimous, was made for his recall, to which the Government acceded. The Duke of Wellington sent for Sir Charles Napier, who announced his readiness to start at once; and he was sent out to India to supersede Lord Gough as Commander-in-Chief at once. But ready as old fighting Charley was, the distance to India interposed an obstacle which saved the gallant soldier who was to have thus been disgraced, from a bitter mortification, and which enabled him to retrieve his fortune, and deliver a death blow to his determined enemy. It was necessary for Gough to give his troops rest, and make good damages and restore confidence to his army and for nearly a month, the British General watched the Sikhs who manoeuvred behind a great cloud of cavalry. On the 12thFebruary the Sikhs evacuated their fortified camp, compelled possibly by scarcity of prov,isions, and marched towards the ford of Wezerabad on the Chenab. Here they were headed by Wished's force from Mootlaw, and they there, on 20th February, took up a position of Goojerat, between the Chenab and the Jhelum. Shere Sing now united had about 60,000 men of all sorts, but only 59 guns. Lord Gough resolved to attack the next day. He had with him about 25,000 men, but on this occasion he had the advantage of high ground, as the Sikhs' artillery was badly placed and exposed to the superior service and action of the British guns, which far outnumbered them. Gough halted his infantry out of fire and advanced his guns. "The cannonade," he says, "now opened upon the enemy was the most magnificent I ever witnessed, and as terrible in its effects." The Sikhs' guns were served with their customary rapidity, and the enemy well and resolutely maintained their position, but the terrible force of our fire obliged them, after an obstinate resistance, to fall back. I then deployed the infantry and ordered a general advance, covering the movement with my artillery as before. Penny's Brigade of the 2nd Europeans, 31st and 70th Native Infantry Part of Harvey's Brigade, led by Franks, with Her Majesty's 10th, broke in upon the centre of the enemy's lines, and as the Campbells Lord Clyde's Division came sweeping round the town of Goojerat on one side, and the Bombay troops on the other, the Sikhs gave way and fled in utter rout, leaving in our hands all the guns but two, and enormous quantity of ammunition etc. This great victory was gained with the loss of five officers killed and 24 wounded, and 92 killed and 682 men wounded. The pursuit was vigorous, but the enemy, pouring through the Khoree Pass, succeeded in crossing the Jhelum river and General Gilbert did not succeed in getting over with his light guns until the 5th March, when the British prisoners of Attock, who had been in the hands of the Sikhs, came into camp to announce that Shere Sing was ready to lay down his arms. On the 14th, the Khalsoo passed through our lines, unarmed and broken. The immediate consequence was the annexation of Punjab. The Governor-General issued a proclamation, in which he said: "The Government of India has no desire for conquest now, but it is bound in its duty to provide fully for its own security, and to guard the interests of those committed to its charge. To that end, and as the onl.y sure. mode of protecting the State from the perpetual occurrence of unprovoked and wasting wars, the Governor-General is compelled to resolve upon the entire subjection of a people their own Government has long been unable to control, and whom, as events have shown, no punishment can deter from violence, and no acts of friendship conciliate to peace. The Maharajah, Dhuleep Sing, was treated with consideration, but Moolrag, the ex Wewan of Mooltan, was found guilty of aiding and abetting in the murder of Mr Van Agruw and Lieutenant Anderson, and was sentenced to imprisonment for life. Votes of thanks to the officers and men of the British Army engaged in the campaign in India were agreed to by both Houses of Parliament, and Lord Gough was as much eulogised as he had been censured.

So poor old Charlie Napier had no show of a fight. He

passed the station in which my regiment was, and nobody knew

who he was. He went to the sergeant of the main guard and

ordered him to turn out the guard, telling him who he was.

The guard was turned out with the colours. The old General

nearly cried over them. He was major in the regiment at

Corunna. Thus ended the second campaign against the Sikhs -

as brave a race of men as can be, and who stuck to the

British throughout the whole of the mutiny. Our regiment was ordered back again to its old station at Amballa.h for a short period, where we went into cantonment again, which we found very tame and quiet, with plenty of breaking in young horses, riding school and foot drill. We got our six months batty money. As most persons may not know what batty means I will explain what it is. Money allowed by Government when an army has been on campaign and succeeded. Each man gets 38 rupees, counting each rupee as two shillings, or 3.16.0 each for the six months. For the campaign of 1845 and 1846 the army got 12 months' batty, 76 rupees or 7.12.0. but what an army that does not succeed gets I cannot tell as I never knew; but I don't think much. However there is always an allowance of liberty allowed at those times, for the sooner the money has gone the better. Our next move was back again into the Punjab to a place called Wuzeerabed, near the river Indus, doing a sort of garrison duty until the beginning of 1853, when our regiment, 3rd Light Dragoons, broke up for Home, when we opened for volunteering. The men could volunteer to any Cavalry Regiment they liked. There were a good number went to the 9th Lancers also the 17th Lancers - that was at Bangalore in Madras. But scarecely any to the 14 Light Dragoons as they were not liked. I did not volunteer myself as I had had enough of India, and 12 years is a pretty good spell, so our regiment marched to Mooldan, on the Indus. Gave up our horses and accoutrements, went on board some large flat- bottomed boats with a flat-bottomed steamer, and struck down the Indus for Karachi, a seaport of the Sind, and a nasty sandy station passed Sukuo and Rory Bukka and Hydrabad the capital of Scinde. Stayed about a week at Karachi, Went on board the Somerset which took 100 days to reach Gravesend. Had terrible bad rations on the yoyage, all the salt beef was condemned, awful bad Biscuits like flint and black, ate the salt pork and only had one barrel left when we reached Gravesend. Old Sir Colin Campbell came with us to Karachi; you would think he was some little old farmer. He was then colonel of the 98th Regiment but one of the real old stuff.

At length, Richard arrived at Gravesend and took the train to Stroud which was near Chatham. From there they were ordered to the bomb-proof shelter at St Mary's to await further orders. Major General Sir R. Dick Brigadier General Taylor General McLaren and 13 officers killed and 100 of our officers wounded. Fights: Punniar: 29 Dec 1843 medal Aliwal: 1846 medal & bar  Sobraon: 1846 medal  Passage of Chinial 1849 ??? Ramnagar 1848  Chillionwala  Goojerat  Click here for Richard's next service years in England

and replace # with @ in my address. All pages have Sound and replace # with @ in my address. All pages have Sound |

The retreat of the Sikhs from Ferozeshah, the army a

short rest, and then took up a position at Sabraon, a village

on the banks of the Sutlej River, and made a very strong

entrenchment there. So strong, in fact that our leading

Brigade could not get into it, so the army waited for some

heavy battering guns from Delhi. By the time the Meerut

division had arrived at the front, and as the cantonement of

Loodiana was in danger of being attacked, and the enem}- was

on our side of the river, we were ordered off to its

protection as there were no troops there but one Seapoy

regiment, and women and children under the command of General

Sir Harry Smith. Also some recruits and women and children

from England.

The retreat of the Sikhs from Ferozeshah, the army a

short rest, and then took up a position at Sabraon, a village

on the banks of the Sutlej River, and made a very strong

entrenchment there. So strong, in fact that our leading

Brigade could not get into it, so the army waited for some

heavy battering guns from Delhi. By the time the Meerut

division had arrived at the front, and as the cantonement of

Loodiana was in danger of being attacked, and the enem}- was

on our side of the river, we were ordered off to its

protection as there were no troops there but one Seapoy

regiment, and women and children under the command of General

Sir Harry Smith. Also some recruits and women and children

from England.