The regiment took the train for Stroud near Chatham, the Gravesend

station I had left nearly 16 years before when I was a mere boy on a wet

miserable day to Gravesend on the 25th October 1837. There was no

railways to carry you, so we were ordered to St Mary's Bomb Proof

Barracks at Brompton, and there we remained until we could be ordered to

some home station.

April 1853. While the 3rd Light Dragoons was lying in

St Mary's barracks with very little money and having nothing to do but

building castles in the air, I took it into my head that if I could get

back into the infantry what a good thing it would be for me. So I spoke

to my comrades about it, which they approved of as I knew all the

infantry drill, as well as I knew the Cavalry drill and our regiment

being over the Home strength, I should not have much trouble of getting a transfer.

Another thing stood in my favour. On infantry

regulations, which was my time of service would be reduced

three years. as an infantry soldier has to serve 21 years,

while a cavalry soldier has to serve 24 years for the same

amount of pension.

There was only the depot of one regiment that I knew

anything about, and that was the depot of the 51st Regiment,

with which I went out to Australia with the convicts in 1837.

So the next morning I dressed myself and went to

Chatham Barracks and saw the captain of the depot, and asked

him if he had any objection, if I could get a transfer, of

taking me into his regiment. He said he had not but would be

very glad if I could get transferred the same time there was

another officer of the same regiment that went out in the

convict ships with us; - it was the son of Lord Erskine, the

great Chancellor of England. He was the Hon David Erskine

and remembered me very well. I then had to apply to my own

commanding officer to ask if he would allow me to be

transferred to the 51st Foot. He said he was very sorry to

lose me as I was a good conduct man, and wearing good conduct

stripes, but as it was for my benefit, and the regiment so

much over its Home strength he would let me go, and ordered

the Adjutant to make out an application for me, and to send

it forward to the Horse Guards at the end of the month of

April 1853, and orders came for me to be transferred to the

51st King's Own Light Infantry, the depot lying at Chatham.

When the regiment returned from Burmah shortly after

the war in that country, the regiment was ordered to

Manchester by train. Having arrived at Manchester, we went

into Salford Barracks, and went through the routine of

garrison drill. Shortly afterwards I was sent to Sherborne

on the recruiting service in Dorsetshire, a duty I very much

disliked, and afterwards to Bridgwater in Somersetshire when

myself and party were called in, as the regiment was under

orders for the Crimea. At the time I had been promoted to

sergeant (1855.) We embarked at Liverpool on board the

steamship Jumna, and shortly arrived at Malta, where we

disembarked and did duty there until the following year,

when the Crimean campaign ended.

During my stay at Malta a small incident occurred which

is worth recording. I was one day ordered to be orderly

to a garrison court-martial which sat in the town of Valetta,

the capital of Malta. By chance the court-martial was

postponed and a French vessel came the night before, and some

of the troops on board were allowed to come on shore,

especially the non-commissioned officers, and fine fellows

there were. They spied me at once, and seeing the medals on

they collared me; one took me by one arm and another by the

other arm, a couple walked behind. I could not speak French

and they could not speak English, so we tried to work by

signs. They lugged me into a wine shop and made me drink

wine, all the time. They in French asked me a lot of

questions.

They then took me again by the arms, and we walked all

over the town. At last I made them understand that I must go

home or I should get into trouble, so we parted the best of

friends. Had one of the officers seen me, it is most likely

I should have been tried by court-martial myself.

1856. Shortly after this the Crimea war ended, and as

our regiment had not been long at Home, we were ordered back

again, but went to Ireland. We landed at the Cove of Cork,

and went to Buttewent, about 22 miles from Cork.

We stopped there a short time, when a mutiny broke out

in the North of Tipperary Militia, which had mutinied about

some fancied thing the Government did not let them have.

However they would not obey orders but marched up and down

the town, their bands playing and it got so bad at last

their officers had to fly for protection to the Town Gaol,

but there was a greater misfortune than that, a detachment of

the 40th Depot was sent to quiet them when they took to

their barracks, shut the gates and defied them. An old

soldier of the 40th regiment happened to put his eye to the

keyhole of the gate, and one of the mutineers shot him

through the head.

We were ordered up to North Tipperary at once, went by

train to Templmore the first day, and marched to Nanah the

next, 22 Irish miles. The gates were opened and a sad sight

it was to see a lot of young Irish lads that composed their

regiment. But there is no sympathy for mutineers let them be

who or what they are. Some were transported and some got

long periods in gaol and some minor punishment. The North

Tipperary was disbanded and has never been organised since.

Stopped about a week at Nanah then back again to Templemore.

Away off to Dublin and was stationed in Ship Street

Barracks, and shortly after to Beggars Bush Barracks at

Donnybrook. Remained a short time there, ordered to the

Curragh of Kildaw into camp. Was stationed there about 8

months. The regiment was ordered to Dublin again and

stationed in the Royal barracks. I was sent as orderly to

General Gascoigne.. A very nice easy billet, nothing to do

but carry a few orders, while the regiment was out at drill

in the Phoenix Park, with plenty of guard mounting, and I had

the pleasure of seeing them passing the General's quarters.

But our time grew short at Dublin, as the mutiny broke

out in India and the regiment was ordered out at once

to India. Of course there is a lot to do when a regiment is

ordered abroad, and takes some time to get ready.There were

general inspections, and general doctors' inspections, to

weed out all those that were unfit for foreign service and to

be left behind in the Depot. I still kept my billet to

General Gascoigne, but had to attend medical inspection but

fortunately or unfortunately I had a large boil just under my

jaw, and had to wear a black silk handkerchief instead of a

leather stock.

I suppose I looked rather a queer looking orderly

sergeant. However, I did not feel very heroic going out to

India again as I had had 16 years of it already, and having

been not long married and between 18 & 19 years of service I

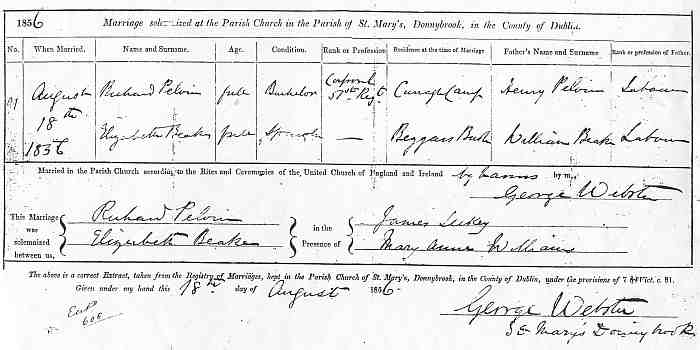

thought it rather hard.  (St Mary's Church, Donnybrook where Richard Pelvin married Elizabeth Beake 18th August, 1856)

(St Mary's Church, Donnybrook where Richard Pelvin married Elizabeth Beake 18th August, 1856)

So I attended medical inspection, and the General,

general doctor, colonel and regimental doctor came along

inspecting. General Gough spoke to me. He was in the 3rd

Light Dragoons as Captain. He gave me great pleasure when I

told him that I had belonged to his regiment as I was the

only soldier that had so many medals in the 51st regiment.

All the staff looked and I suppose the wondered what was the

matter with me. The regimental doctor turned back to speak

to one of the men and the staff passed on and I began to

grumble at having to go out again, when who should come along

but the regimental doctor. He asked what I was grumbling

about. I told him I had been 16 years abroad and had about

19 years' service when he looked surprised, and went on after

the colonel, brought him back. They never asked me what was

the matter with me, The colonel said, "Fallout to the right,

Sergeant Pelvin." The doctor said "It is no use sending such

men out to India - they will die in about a week." I

laughed in my sleeve as I then was to be left in the depot.

My orderly-ship soon came to a close after this, and I

was ordered to Belfast on the recruiting service again, which

I so much disliked, but was soon recalled to Dublin again

just on point of my regiment embarking to go with the depot

to England. Shortly after the regiment embarked we were

ordered to Chatham and in about three weeks were ordered to

WeImer, near Deal, where the Duke of Wellington died at

Walmer Castle. We remained here about a year and was then

sent to Chichester near Portsmouth where I stayed about

three months, when I put in a claim for my discharge, after

serving Her Majesty for 21 years and 330 days, not including

three months I had to serve for not being 18 years old when I

enlisted, which would make my service twenty-two and a half

years.

I then went and joined the staff of the West Kent

Militia at Maidstone, where I was made pay sergeant of a

company. Just at this time the volunteers were coming into

notice, great numbers of gentlemen and middle class were

going in for volunteering, and a fine body of volunteers was

got up in defence of the Old Country.

Myself and our sergeant-major were sent to a School of

Musketry of Hythe for three months to study musketry

instruction. When we returned we were appointed instructors

to volunteers - the sergeant-major to Maidstone and myself to

Tunbridge Wells in Kent.

I had a splendid company at Tunbridge Wells, gentlemen

of worth and position, who had to find their own uniforms.

Belts and rifles were found by the Government. They were so

eager to learn their exercises that they paid for extra

drills, so my time was well occupied with that and the

militia. But I had to go to the training of my regiment when

it came.

The volunteers wanted me to take my discharge from the

militia, but our colonel would not let me go, so I had to go

on drilling volunteers. At last they would have a drill

instructor of their own, and I had to leave which I was very

sorry for. They made me a present of a very nice watch and

guard, in token of their satisfaction of my service, which I

have carried it to this day, inscribed, "Presented (by the

17th Kent Turlbridge Wells Rifle Volunteers, to Sergeant

Richard Pelvin in testimony of his efficient service as their

drill instructor, 1860."

After this I had three sub-divisions to drill, one at

Lamberhurst, one at Breachly and one at Yalding, Kent, where

I attended once a week, but of all the men I had to manage

the worst was my company in the militia, which was a very

tough lot. They were recruited from Deptford, Dartford,

Greenwich and Woolwich, and it would break an instructor's

heart to make anything of them. The company was composed of

costermongers, hawkers, loafers, sharpers etc etc. Such a

motley crowd I never had to deal with, as the saying is they

would take the eye out of your head. I was always very

careful when paying them their day's pay and they were as

stupid as owls. However, I was very glad when the annual

training was over, and they went to their homes.

I served in the West Kent Militia nearly four and a

half out of five years, and then I thought it was nearly

time to have a change, so I made up my mind to emigrate

somewhere.

Myself and Mrs Pelvin had a talk about it. As it

happened a minister of the Gospel had been giving a lecture

on New Zealand at a village called Pembury just outside

Tunbridge Wells, and I thought I would see him and have his

advice. He thoroughly advised me to go to Canterbury, New

Zealand, as he said it was a better place to emigrate to than

Nelson, where he had come from.

From here I went to Charing Cross, London, to see a Mr

Marshman, the agent for Canterbury, and he advised my to

apply for my discharge from the Militia, which I did on the

1st July, 1863, and went on board of the Lancashire Witch and

sailed from the East India Docks on the 2nd of July 1863.

Mr Marshman was very kind. He made me acquainted with

the Doctor who took me under his wing. Dr McLean was a

thorough gentleman; I have known him to send his dinner from

the cabin table to some of the sick ones (we had about 26

deaths on the voyage), to see if he could tempt any of them

to eat. The doctor and myself were about day and night,

although he could scarcely crawl, as he was ill himself. We

arrived at Timaru at last, and landed on October 1863. The

captain made me a present of 5, the Government 5, (and the

Government also made Mrs Pelvin a present of 5.)

I had now to commence a new career in New Zealand with

a wife and four young children, on a bare piece of country

which we have worked to our best ability, and have succeeded

to some extent.

Mr Woolcombe (Resident Magistrate) put me in charge of

the emigrants that landed at Timaru, about 200 in all, until

they could get employment, which kept me at the emigration

barracks for nearly six months. I took my family to the

place named Claremont leased from the Provincial Government

40 acres, about four miles from Timaru where I may say I

first started my career as a colonial.

Richard Pelvin - events that occured in his life